Life of a Zeppelin Part 1: Was the Hindenburg Fire a Case of Sabotage?

An Opinion Piece by James Rousse

For the last few years I have been reading and meditating on the subject of hydrogen-filled dirigibles, but nothing really developed from this sideline interest for quite a while; however, an email that I received from a friend and fellow Thule Society contributor inspired me to write an article about this neglected avenue of technology.

Zeppelin Lives Matter

The Hindenburg fire and subsequent crash happened more than 84 years ago as of 2021, yet this storied dirigible fire still keeps resurfacing in articles and television specials. Shortly after the Hindenburg fire happened, this event immediately became big front-page news across newspaper editions around America and the rest of the globe, at least to some degree. The Hindenburg tragedy was also recorded by four different mainstream news agencies and then shown on news reels at movie theaters around America and points beyond. Back in the 1930s, news traveled to the public through newspapers that were connected to one another by wire services, but radio was also a major media format back then, large circulation magazines such as Reader’s Digest were also around, and newsreels that were shown in theaters before feature movies began were also a significant part of the media landscape in those days; therefore, information about the Hindenburg tragedy was shared pretty much around the world on all of the major media formats of that era almost as soon as it happened.

Indeed, the Hindenburg tragedy became a huge media sensation almost as soon as it happened, and the after-effects of this fire and the subsequent crash have remained with the world as the decades have passed. Despite the actual event of the Hindenburg crash being a major media storm, the cultural impact of the Hindenburg in particular, and hydrogen-filled dirigibles in general, were both amazingly powerful before the Hindenburg caught fire. Before the Hindenburg caught fire and then crashed in front of a crowd of more than 1,000 onlookers with all of the big media organizations recording the event, a few huge passenger dirigibles owned the sky and captured the public’s imagination to an amazing degree.

A Public Relations Disaster and a Big Embarassement for Hitler, National Socialism, and the Nation of Germany

For right or for wrong, many people now look back on the Hindenburg Tragedy and view this event as a sort of portend from the devine that Hitler’s government and the nation that he led was going to be consumed in a giant storm of fire, just like the Hindenburg was, so there seems to be an added layer of intrigue to this storied tragedy. The Hindenburg fire certainly held quite a bit of metaphorical significance because this impressive vessel was a potent and postive rhetorical symbol of National Socialist Germany’s technological prowess, so the Hindenburg’s destruction was a notable public embarrassment to both the German nation and the German people. It also comes as no surprise that news of the Hindenburg tradgedy was reported by the German media establishment of that era; however, this story was deliberately given as little attention as was possible.

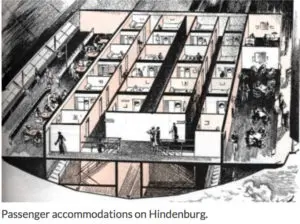

It is easy for people living today to forget that during the 1930s hydrogen dirigibles were acutally the most technologically advanced and capable aircraft. For example, the Graf Zeppelin was capable of crossing the entire Pacific Ocean in just a few days without making any stops, and such a capability actually remains a notable achievement clear up into the present day. Another issue to consider is the fact that the Hindenburg transported its passengers in relative luxury by offering such amazing ammenities as a piano bar, a fine dining room, and at least decent private passenger cabins. Even to this day, aircraft still do not offer the general public such notable luxury accommodations as those found on the Hindenburg, so the Hindenburg was in truth a timeless wonder that oozed sophistication, showcased technological prowess, and offered travel with a surprising level of speed. The Hindenburg could be considered something akin to the Titanic of the Sky as well as a truly magical and timeless ship of dreams.

The image posted above is a distance photograph of the Hindenburg fire. Image courtesy of airships.net

Another major issue associated with the Hindenburg Disaster is the fact that this event seemed to have put a complete stop to any further development in the field of hydrogen-filled dirigibles, and this was the case because the Hindenburg’s destruction truly shattered the public’s faith in these types of aircraft. True, dirigibles still survive to this day in the form of small blimps that lack full internal skeletons, and yes, there are now a limited number of semi-rigid helium-filled derigibles in operation, but the comparatively small helium-filled dirigibles that occasionally grace the skies during our present days are not much use for mass transportation, nor are they much good for cargo hauling; in other words, today’s blimps are basically just novelties and toys that are good for a little bit of sight-seeing and the odd bit of event coverage. Yes, dirigibles see little practical work in the present times, but this state of affairs does not have to remain. Despite the lingering doubts that were spawned by the high-profile Hindenburg fire, I still believe that hydrogen-filled dirigibles will surely make a comeback.

Image of the Goodyear Blimp covering a college football bowl game in Florida courteys of multivu.com

The helium-filled blimp shown in the photo above is really quite small and lacks the ability to perform real work such as moving passengers in decent numbers or hauling freight in a meaningful manner. The blimp seen above is really nothing more than an advertising platform and a place to mount a few cameras. Image courtesy of journal.classiccars.com

The Cultural Impact of Hydrogen Filled Dirigibles Before the Hindenburg

In the years preceding the Hindenburg crash, hundreds of flights were made by large hydrogen-filled dirigibles that flew the flags of different nations; for example, Britain made their own hydrogen-filled dirigibles, and America operated a few large helium-filled dirigibles. Before the Hindenburg burned and crashed, huge hydrogen-filled dirigibles graced the skies above major world cities such as New York, London, Rome, and Rio De Genaro. The company that made the Hindenburg, which was called Luftschiffbuat Zeppelin, began producing commercial passenger-carrying hydrogen-filled dirigibles back in 1908, and during the following years, the skies above many of the world’s largest and most iconic cities such as Tokyo saw great hydrogen-filled airships grace their horizons.

The image above shows the Graf Zeppelin hovering over Tokyo. Image courtesy of lazzo51 on flickr.com

The artistic rendering of the Graf’s visit to Tokyo is furnished courtesy of thetokyofiles.files.wordpress.com

It is also worth mentioning that Zeppelins were used for survallence missions in addition to ground support initiatives along with bombing campaigns against towns and cities during World War I, so Zeppelins had already made quite a cultural impression for the better or for the worse long before any major civilian publicity tours in the years between the two great 20th centurey wars in Europe were ever made. As listed on a 2015 articele from (((The Daily Beast))) (yes, I know) called “The Zeppelin That Bombed London and Changed the World,” Zeppelin bombing raids against England during the first World War dropped an estimated 5,000+ bombs which officially killed 557 people and injured 13,358, so although these raids had little real impact on the war’s outcome, they did certainly make quite an impression on the public. It is also important to remember that Zeppelins not only bombed towns and cities in England and Scotland during World War I, but the city of Paris, France was also subjected to Zeppelin bombing missions and other continental European cities such as Bucharest, Romania were additionally hit by bombs dropped from German Zeppelins.

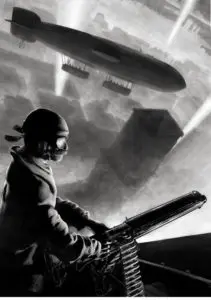

The photograph above shows a World War I German militiary Zeppelin in flight. Image courtesy of K P S on pinterest.com

The image above is a painting that depicts the German Schutte Lanz SL2 Zeppelin bombing Warsaw, Poland in 1914. Image courtesy of en.wikipedia.org

Artwork of a Zeppelin bombing raid over London courtesy of reddit.com

The image above shows the aftermath of a World War I Zeppelin raid upon the town of Yarmouth, England. Image courtesy of historycentral.com

The photograph above shows damage to a residential area on Estreham Road in the Streatham section of London, England. The damage shown above was wrought on Speteber 24th, 1916. Image courtesy of networks.h-net.org

The photo seen above is an archival image of a January 29, 1916 Zeppelin air raid on the city of Paris, France. Image courtesy of today-in-wwi.tumblr.com

During the years between World War I and World War II, the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin company, which was the outfit that manufactured the German Zeppelins, saw the most success with the Graf Zeppelin which passed the beginning of its building program in 1926 and saw the end of its building program with an official launch on July 8, 1928. Soon after its formal commissioning, the Graf Zeppelin made six short-distance testing flights around Europe, then completed its first intercontinental flight to Lakehurst, New Jersey on October 15th 1929 after logging just under 112 hours of flight time.

After completing its first intercontinental flight, the Graf Zeppelin made several high-profile publicity tours around Europe and the Mediterranean region. In the spring of 1929, the Graf Zeppelin completed a publicity tour around the Mediterranean basin which included stops in Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and the Dead Sea. Not surprisingly, the sight of this huge airship hovering over the cities of that region made quite an impression on the local populace, plus the Graf’s presence at these Middle Eastern ports of call set the stage for many breathtaking photographs that were circulated far and wide in those years and still capture the public’s imagination to this day.

The photo posted above is an archival remnent of the Graf’s visit to Juruselum. Image courtesy of timesofisrael.com

As noted in Airships.net, in August 1929, the American newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst paid half the cost of a world-crossing publicity tour for the Graf Zeppelin. Hearst also included four hand-picked staff members from his organization on this historic flight, which included a well-known British socialite and journalist named Lady Grace Drummond-Hay and a professional photographer named Robert Hartmann. Hartmann was commissioned to record the Graf’s around-the-world trip in a format of photos and movie film that was earmarked for distribution across all of Hearst’s media empire. Hearst’s sponsored circumnavigation voyage for the Graf Zeppelin began in Lakehurst, New Jersey on August 7, 1929; then continued on to Freidrichshafen, Germany, after that, the Graft Zeppelin went onward to Tokyo, Japan. The Graf Zeppelin arrived in Tokyo on August 19, 1929 and was greeted by a crowd that was estimated to be around 250,000 onlookers.

Image of Lady Grace Drunnond-Hay courtesy of airships.net

Image of Lady Grace Drummond-Hay posing for a photo in one of the Graf Zeppelin’s propeller pods furnished courtesy of airships.net

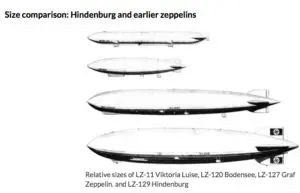

Image that compares the Hindenburg to previous Zeppelins courtesy of airships.net

After making a stopover in Japan from August 19th—23rd, the famed Graf Zeppelin next proceeded to finish the first nonstop air crossing of the Pacific Ocean, which took only 79 hours. A nonstop aerial crossing of the entire Pacific Ocean was a remarkable achievement for its time, and this trip was culminated with a timed arrival that included flying over the Golden Gate straights which rest between the city of San Francisco and the southernmost tip of Marin County on the other side of the San Francisco Bay. As planned, the Graf Zeppelin arrived at the Golden Gate waterway right as the sun was setting. Although the Golden Gate Bridge had not yet been built, the Graf’s sunset arrival in San Francisco furnished journalists with countless spectacular photo opportunities, as it was intended to do. The Graf Zeppelin made a spectacular timed arrival over San Francisco; however, this cruise ship of the sky never landed in the Bay Area, but instead proceeded to land in Los Angeles after making a slow chug down the coast of California. Next, the Graf made a three-day port of call in Los Angeles, then set sail for its final return journey to Lakehurst, New Jersey.

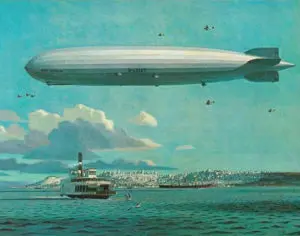

The photo above shows the Graf Zeppelin hovering over the Golden Gate waterway that seperates the city of San Francisco from the headlands of Marin County to the north. Image courtesy of pbagalleries.com

The image above is a pianting made by Stan Galli that comemorates the Graf’s visit to San Francisco. Image courtesy of This Week in California history group on Facebook.com

The last leg of the Graf’s trans-world journey ended on August 29th 1929 and involved making an overland crossing of the North American continent. The last leg of the Graf’s circumnavigation included stops in 5 American cities, and among these stops were the cities of El Paso, Texas; Chicago and Detroit. In total, this first-of-its-kind world-crossing journey had taken only 12 days, but logged 20,651 miles while traveling from Lakehurst, New Jersey; around the globe, then back to Lakehurst again. The Graf’s trip around the world was quite a spectacular feat for its time — or any time for that matter — so, this event truly put the nation of Germany on the cultural map in those days. The Graf’s popular circumnavigation of the world certainly provided fodder for endless journalistic articles and furnished countless spectacular photographs that graced the covers of big newspapers and high-circulation magazines alike around the world, which in turn brought a huge amount of publicity and social prestige to Zeppelins in general and the nation of Germany in particular.

The above photo shows the Graf Zeppelin hovering over the city of El Paso, Texas. Image courtesy of The El Paso County Historical Society on Facebook.com

Image of the Graf Zeppelin flying over the city of Detroit courtesy of Sibhi Yasbeih on Pinterest.com

After completing its groundbreaking trans-world journey, the Graf Zeppelin then made a few publicity appearances in London in the spring of 1930, and following that, the Graf completed a Pan-American tour that started in Spain, proceeded to Recife, Brazil; and then included a final stop in Lakehurst, New Jersey before departing on the return voyage to Spain. In the fall of 1930, the Graf Zeppelin also made a publicity stop in Moscow, Russia where its arrival was greeted by more than 100,00 onlookers who gathered in the city center; interestingly, this event took place on September 11 of that year.

The photo posted above shows the Graf Zeppelin hovering over Wimbley Stadium in London. Image courtesy of N Jocko on Pinterest.com

In the spring of 1931, the Graf made another tour of the Mediterranean basin; except this time, the storied airship made stops in the Egyptian cities of Alexandria and Cairo. During the Graf’s first tour of the Mediterranean, this airship was not given permission to enter Egyptian airspace because of pressure from the British government, but years later, during the Graf’s first officially sanctioned visit to Egypt’s capital city of Cairo, this grand old dirigible posed for photographs where it hovered a mere 70 feet above the top of the largest pyramid at Giza, and an additional photo shoot was took place where the Graf was photographed hovering just 50 feet above Egypt’s famous Sphynx monument. Needless to say, both of these events made for some great photo opportunities which served as fabulous public relations material for the nation of Germany.

The image above shows the Graf Zeppelin hovering over the Great Pyramids in Egypt. Image courtesy of Carl Guderian on Flickr.com

The image of the Graf hovering near the Sphinx in Egypt. Image courtesy of snopes.com

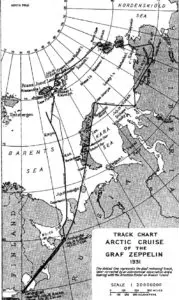

After completing its second tour of the Middle East, the Graf Zeppelin performed a high-publicity trip to the arctic ocean region in July of 1931. The Graf’s 1931 mission to the arctic included mapping Franz Joseph Land from the air and measurements of the Earth’s magnetic field were taken by a Russian scientist named Professor Samoilowich. The Graf’s artic expedition also carried an assortment of well-known journalists such as Arthur Koestler, so this trip was a high-profile public event as well as a legitimate scientific expedition. After the arctic expedition was finished, the Graf Zeppelin began its regular service to Brazil, which it continued until its final decommissioning in 1937.

The image above shows the Graf Zeppelin hovering above the Arctic ocean. The photo above was taken from the deck of the Russian ice-breaker Malygin. Image courtesy of airships.net

The imag above shows a mapped route of the Graf’s 1931 Arctic expedition. Imag courtesy of researchgate.net

Image of the Graf Zeppelin hovering over Rio de Genero Brazil courtesy of wikipedia.org

The Graf’s Association with the Third Reich

Like its larger sibling, the Hindenburg, the Graf Zeppelin was also actively used for public outreach initiatives after Hitler assumed the office of German Chancellor in January of 1933. Like the Hindenburg, the Graf also made regular appearances at annual Nuremburg rallies and graced the skies when Hitler gave public speeches in front of crowds numbering in the hundreds of thousands. During the Nuremburg Rallies, both the Graf and the Hindenburg would hover above these huge crowds, take photographs of the events, and even offer sight-seeing tours to a few lucky participants. Thus, both the Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg became high-profile institutions that were very closely associated with Germany’s National Socialist government for the better or for the worse; therefore, these potent symbols of National Socialist Germany were certainly attractive targets for Jewish saboteurs and terrorist groups.

The image above shows the Graf Zeppelin hovering over a Nuremburg rally. Image courtesy of almaty.com

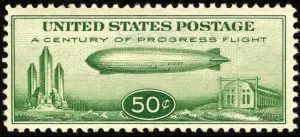

The Graf Zeppelin was commandeered by Joseph Goebbels soon after Hitler assumed the Chancellorship of Germany, and the Graf accentuated the Berlin festivities during the May 1, 1933 “Tag de Nationalen Arbeit,” or the National Socialist version of Labor Day. Later that month of May passed, the Graf flew to Rome as part of a diplomatic visit between Joseph Goebbels, Benito Mussolini, and other high-ranking members of the Italian Fascist government. In October of 1933, the Graf completed a brief tour of the United States at the invitation of the Chicago World’s Fair Committee. That same year, the World’s Fair chose the moniker, “Century of Progress International Exposition.”

The photo above shows the Graf Zeppelin in the skies over Chicago. Image courtesy of photos.com

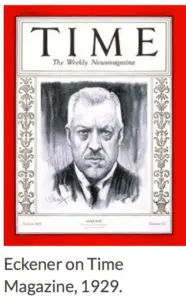

Hugo Eckner, who was the president of the Zeppelin company at that time, agreed to take his company’s large dirigible on a short tour of North America in 1933, which included a stopover at the World’s Fair expo, but Echener only agreed to this arrangment if the American postal service would issue a line of stamps commemorating the Graf’s visit, Eckner also included a proviso in the Graf’s contract with the World’s Fair committee that would guarantee half of the profits garnered from sales of this limited-edition American page stamp would be gifted to the Zeppelin company. The Zeppelin’s planned North American tour was a politically explosive and controversial event at that time, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt initially opposed having any German Zeppelin ply American skies at all, but Roosevelt was especially opposed to having a commemorative stamp of this event issued.

The image above shows the American comemorative stamp for the Graf Zeppelin’s vist to the Chicago World’s Fair. Image courtesy of commons.wikimedia.com

Despite strong disagreements within the top levels of the American postal service, the Graf was eventually granted permission to visit the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago, and an agreement was also made to print a line of official American postage stamps that would celebrate the event. The Graf’s tour of North America that October was uneventful, but when the Graf was gracing the skies above Chicago, this grand Zeppelin only flew circles around the World’s Fair expo in a clockwise direction so that the sides of this craft which had swastikas painted on the steering fins would not be visible to people on the ground. When the Graf Zeppelin visited the Chicago World’s fair in October of 1933, one side of the steering fins still had the old German Imperial flag flying, but the other side flew the swastika.

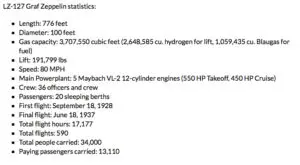

All in all, the Graf had logged more than 590 flights, transported more than 34,000 passengers, and traversed more than 1-million miles before finally being forced into retirement in 1937 following the Hindenburg disaster. It is worth noting that the Graf Zeppelin was flying over the Spanish Canary Islands when news of the Hindenburg disaster reached the Zeppelin’s crew. After receiving news of the Hindenburg tragedy, Captain Hans von Schiller followed his orders and promptly returned the craft under his command to Germany. Needless, to say, none of the passengers aboard the Graf were notified of the Hindenburg disaster until well after the Graf had safely landed in Germany. After returning to Germany in 1937, the Graf Zeppelin never carried passengers again and this fine craft was eventually broken up and used as a source of aluminum for the Luftwaffe. It is also worth noting that Hermann Goering, who was head of Germany’s airforce during World War II, had a particularly stong personal distaste for derigibles in general, so he wanted to see all of the grand German derigibles scapped so that their aluminum skeletons could be put to better use.

The image above lists the basic stats for the Graf Zeppelin. Image coutesy of airships.net

The Hindenburg

Plans to start building the Hindenburg began in the fall of 1931, and the proposed construction of this larger dirigible was inspired by the success of the Graf Zeppelin. However, unlike the Graf, the Hindenburg was designed to operate with helium as it lifting gas, so the Hindenburg was designed with even larger proportions in mind than the Graf that would compensate for the lesser lifting capacity of helium.

The image above shows the Hindenburg in flight over Berlin. Image courtesy of dirkdeklein.net

The image above show the Hinenburg flying over the German city of Kohln. Image courtesy of dirkdeklein.net

The design specifications of the Hindenburg called for using of helium as the lifting gas because there had been a troubling rash of hydrogen filled dirigibles that caught fire and crashed with deaths that followed. The crash of Britain’s hydrogen-filled R 101 dirigible on October 5, 1930 served as a warning about the problems associated with using hydrogen as a lifting material. The R 101’s crash killed 48 of the of the 54 people on board, and these deaths were attributed to a hydrogen fire, not to the relatively moderate crash landing which happened in Beauvais, France. Interestingly, the Zeppelin company bought 5,000 kilograms of dura-aluminum that were salvaged from the R 101’s wreckage, yet due to internal financing problems, the first flight of the Hindenburg did not happen until March 4, 1936.

Image of Britian’s R 101 hydorgen-filled dirigible courtesy of airships.net

Many readers may be wondering why the Hindenburg was not filled with relatively safe and inert helium gas as opposed to potentially volatile hydrogen. As listed on the Real History Channel’s website, the Hindenburg was not filled with helium because America was the only nation that actually had access to helium at that time, and an American Jewish governmental administrator named Harold Ickles, who was an avowed Marxist, a died-in-the-wool loxist, and a rabid hater of Germans, had made sure that the Germans would never gain access to any American-produced helium; well, certainly not on his watch anyway!

Imag of Harold ickles courtesy of content.time.com

Unfortunately, the only known reserves of helium that were available for large-scale extraction in the 1930s were located in the Panhandle of Texas, the panhandle of Oklahoma, and the southwestern part of Kansas. For those of you who are not aware, helium extraction typically takes place as a secondary pursuit that is associated with drilling natural gas wells; some deposits of natural gas have been found to contain up to 10% helium, but this is rare. Today, the prairie states of America hold 40% of the planet’s helium reserves and the oil kingdoms of the Middle East hold most of the remaining helium deposits.

The Hindenburg’s life was brief, but storied. The Hindenburg took its first flight in March of 1936, and then appeared overhead at the Berlin Olympics in August of that same year. The local turnout for the 1336 Berlin Olympics was estimated to be more than 3 million visitors, but this event was also broadcast on newsreels, radio programs, and this happening was even broadcast on live television in color, so like every installment of the Olympic games, the Berlin olympics of 1936 were a truly high-profile event.

The photo above shows the Hindenburg hovering over the stadium of 1936’s Berlin Olypmic games. Image courtesy of artsandcutlure.google.com

The image above shows the Hindenburg at the 1936 Olympics. Image courtesy of historycollection.com

Image of the Hindenburg at the 1936 Olypics courtesy of airships.net

Besides being one of the stars of Berlin’s 1936 Olympic games, the Hindenburg also made a high-profile flight where it took the German boxer Max Schnelling back from New York City to Germany after he had defeated, and knocked-out, a Black American boxer named Joe Luis. Schnelling’s landmark win happened on June 19th, 1936 in front of a packed crowd at New York City’s Yankee Stadium. After returning to Germany in style on the Hindenburg, Schnelling received a hero’s welcome and met with Hitler in person, so Schnelling’s return to Germany by way of the Hindenburg accentuated what was already a great publicity event.

Diagram of the Hindenburg’s interior courtesy of airships.net

Photo of a Hindenburg passenger stateroom courtesy of airships.net

Image of the Hindenburg’s rather nice dineing room courtesy of airships.net

Image showing one of the Hindenburg’s observation lounges supplied courtesy of airships.net

The image above shows Max Schnelling. Image courtesy of airships.net

The image above shows Max Schnelling and his wife publicly meeting with Adolf Hitler after returning to Germany following his big win over Joe Louis. Image courtesy of history.com

By the end of 1936, the Hindenburg had made 18 round-trip flights between the United States and Germany, and prior to the big disaster in May of 1937, the Hindenburg had made six successful flights including a round-trip from Germany to Brazil and back.

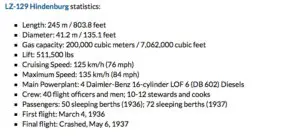

The hindenburg’s stats provided courtesy of airships.net

Images comparing the Hindenburg to otehr aircraft furnished courtesy of airships.net

The Usual Suspects: Means, Motive, & Opportunity

In the beginning, I was quite certain that the Hindenburg fire of 1937 was the result of Jewish scheming and treachery; yet, the more reading I did on the subject, the less certain I was that the Hindenburg fire arose from yet another round of Jewish rascality. Please, do not get me wrong, as the Chief editor for the Thule Society, I am quite well-versed in the ebb and flow of Jewish evil, depravity, and mischief; however, I would not consider myself to by a true scholar of these matters along the lines of such luminaires as Dr. David Duke or Dr. Kevin McDonald. So, let it be said that I am not defending the non-existent honor of the Jewish people when I say that I am not totally convinced the Hindenburg fire in 1937 was simply caused by Jewish malevolence, scheming and hand-rubbing. Indeed, taking a good look at the background information surrounding the Hindenburg fire certainly raises a lot of questions as to whether this event was really a case of sabotage or not.

Image courtesy of bostonglobe.com

A Crucial Point of Note

Airships.net graciously provides a list of 22 hydrogen-filled dirigibles that crashed or caught fire prior to the Hindenburg Disaster. It is also important to remember that airship.net’s list of hydrogen-filled dirigibles which either crashed or caught fire does not include the hydrogen-filled Zeppelins that were lost in combat operations during World War I. A link to all of the specific hydrogen-filled vessels that burned due to hydrogen fires can be found here. The point to consider is that there was a long and troubled record of hydrogen-filled dirigibles catching fire or crashing for whatever reason, and this rotten safety record was wracked-up well before the Hindenburg ever set-off on her maiden voyage, so it is very possible that the Hindenburg fire was not the work of Jewish sabotage.

The Official Story

The Hindenburg disaster is officially recorded in the history books as having started at 7:25 PM on May 6th, 1937; and this disaster took place at the United States Naval Air Station in Lakehurst, Hew Jersey. The death count from the Hindenburg disaster stands at 36, and these official death records were spread amongst 22 fatalities for the Hindenburg’s crew, 13 losses from the passenger list, and one ground-crew casualty. When the Hindenburg made its final arrival in New Jersey, there were 97 people on board with 36 of them being passengers and 61 of them being paid crew members. Interestingly, there were film crews from four news agencies who were present at that time.

During the Hindenburg’s last moments, there were also more than 1,000 spectators present to watch this famous vessel’s first North American arrival for the year of 1937. Indeed, this particular arrival had received an unusual amount of publicity because it marked the Hindenburg’s first North American visit for that year, plus the weather delays from that trip forced the Hindenburg to wait hours until landing clearance was given, which meant that this airship passed many hours of waiting that afternoon and evening by cruising over New York city and the coastline of New Jersey. So, in light of that evening being the Hindenburg’s first arrival in America for that year, plus the hours passed cruising over the five boroughs of New York City, is comes as no surprise that there were also an unusual number of spectators and media people present for that particular landing.

Image of the Hindenburg flying over New York City courtesy of boweryboyshistory.com

Image of the Hindenburg flying over New York coutesy of lazzo51 on flickr.com

As of May of 1937, the Hindenburg had completed 10 round trips between Frankfurt and Lakehurst, New Jersey in 1936, and this same dirigible was also scheduled to complete a total of 18 round trips between Germany and Lakehurst, New Jersey in 1937. Prior to departing from Frankfurt on the first of its scheduled trips to North America for 1937, the Hindenburg had completed a round trip between Frankfurt and Rio De Genaro, Brazil.

The Track Record

Prior to the Hindenburg’s final departure, there was a solid record of safe operation for all of the Zeppelin company’s dirigibles, and since commencing commercial passenger operations in 1908, not one fatality had ever been recorded for the Zeppelin company prior to 1937’s Hindenburg disaster. It is also important to remember that lightning strikes that hit hydrogen-filled Zeppelins were actually a common occurrence, yet these strikes were basically harmless, plus leaks and rips in the hydrogen-filled lifting cells inside of these massive rigid-framed airships were also quite common and easily managed. Thus, it begs the question…what went wrong when the Hindenburg went up in flames and crashed?

What Might Have Been the Cause?

Imae of the Hindenburg fire courtesy of independent.co.uk

After reading many different entries and articles on both Wikipedia and Airships.net, as well as watching PBS’s Nova program about the Hindenburg’s crash, the likelihood that this disaster was the result of Jewish subversion seems ever less probable. Believe me, I am quite well aware that PBS and Wikipedia are outlets that have a bit too much Hebrew influence to qualify as truly reliable sources of information, none the less, both of these sources still furnish some basic facts about the Hindenburg disaster that are solid.

For example, as the PBS special about the Hindenburg disaster notes, during the season of 1937, the German government started to place the highest emphasis on meeting deadlines and keeping time-tables, which looking back in retrospect set the stage for a disaster one way or another. All records indicate that during the night of the Hindenburg’s arrival in New Jersey, bad weather had already delayed the ship by 12 hours due to strong headwinds encountered while crossing the Atlantic, so there was tremendous pressure on the part of the Zeppelin’s flight crew and the American ground crew at the naval air station in New jersey to get that ship landed as fast as possible and then get the passengers off with all haste. It is also worth noting that the Hindenburg had a fully booked flight manifest for its return voyage to Germany and this airship was also scheduled to make yet another high-profile visit to the coronation of England’s King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in London withing about a week of the tagedy.

The night of the Hindenburg’s demise, there were rain storms and some winds to contend with, and in the years since this storied disaster happened, many researchers have uncovered pretty solid evidence that there may have been several weakened, damaged, or even outright defective structural tensioning cables burried within the Hindenburg’s internal superstructure prior to its last flight.

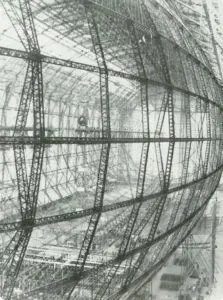

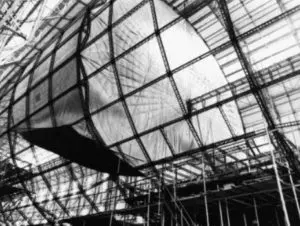

The photograph above shows the interior skeleton of the Hindenburg in the process of assembly. Image courtesy of Julien on Pinterest.com

Countless films of the Hindenburg disaster clearly show the rear part of the Hindenburg sagging noticeably as the great airship approaches the American mooring tower, yet this airship’s captain did not send any riggers back to investigate the matter due to time pressures. In fact, many witnesses noted a pronounced heaviness in the ship’s stern portion more than half an hour before any attempts at a landing were ever attempted, so the theory that making a series of sharp turns caused internal cable breaks which in turn lacerated one or more hydrogen-filled lifting cells does not hold up very well. Despite the fact that there was a pronounced lack of lift in the back part of the Zeppelin for at least 30 minutes before its final landing run was made, there is still strong evidence that some type of hydrogen leak was present in the rearward lifting cells for whatever reason.

The photo above shows the Hindenburg’s internal aluminum skeleton along with a hydrogen lifting cell. Image courtesy of airships.net

The time pressures to get the Hindenburg moored quickly on that day also included the captain’s desire to land this dirigible before another thunder storm showed up and delayed their arrival even further. Other smoking guns for the leaking hydrogen cell(s) hypothesis include the fact that the Zeppelin had vented truly huge amounts of hydrogen from the frontal portions of the craft, and these amounts of vented hydrogen qualified as unusually large amounts for that matter.

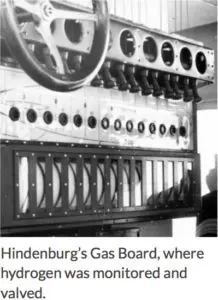

Image of the Hindenburg’s gas board courtesy of airships.net

As listed on Airship.net, Albert Sammt, who was the Hindenburg’s first officer, had released or “Valved” the front hydrogen cells for a full 30-seconds before the Hindenburg’s final landing approach, and Sammt had also released 2402 pounds of ballast water in the front sections of the craft over a series of three consecutive water dumps. The Hindenburg’s Captain Pruss had also ordered six crewmen to take stations at the forward-most part of the Zeppelin after all of the water dumps and hydrogen valving were finished, and this was done in order to help weigh-down the ship’s rising bow, let us keep in mind that this amount of de-ballasting and venting prior to making a landing attempt was a sure-fire sign of trouble.

Image of the Hindenburg’s bridge crew courtesy of airships.net

Numerous witnesses to the Hindenburg Fire, such as an American ground crewman named R.W Antrim noticed signs of leaking lifting cells before the fire started. Antrim was stationed at the top of the mooring mast in Lakehurst during the disaster, and he reported seeing unusual “undulating waves” under the Zeppelin’s skin prior to the big fireworks display. Many ground observers also claim to have seen the outer skin on the top portion of the Hindenburg near to the dorsal controlling fin flapping and undulating before the craft caught fire. Thing is, hydrogen does not actually ignite easily, in fact, it takes a temperature of at least 932 degrees Fahrenheit to ignite this gas, as is listed on the Wikipedia page about the Hindenburg disaster. According the website called rebresearch.com, hydrogen is also a very efficient conductor of heat, so whatever heat that is present tends to get wicked away very quickly and dissipated elsewhere when pure hydrogen is present, so hydrogen’s exceptional heat conducting properties are another factor that makes this gas harder to ignite than most people would suspect.

If the most likely explanation for the underlying cause of the Hindenburg disaster was excessive haste and carelessness on the part of the Hindenburg’s crew and on the part of the airfield’s crew as well, which then lead to a leaking hydrogen cell not being properly investigated and fixed prior to making a landing attempt, then the next question would be this, “What ignited the leaking hydrogen?” Before a discussion concerning the ignition source for the Hindenburg’s stores of lifting hydrogen takes place, it would be best to outline what created the circumstances favorable to a hydrogen fire developing in the first place.

For starters, hydrogen will certainly ignite if it has been mixed with air, and it seems that the leaked hydrogen which was probably causing undulating waves under the upper skin of the Hindenburg on that day certainly had plenty of opportunity to mix with enough atmospheric air to create a properly combustible mixture. Another contributing factor for the disaster to consider is air entering the leaking hydrogen cell(s) and creating a combustible mixture there as well. So, it seems that the lacerated and leaking gas cell(s) at the back end of the Hindenburg had probably filled with enough atmospheric gas to become combustible in their own right in the minutes leading up to the final disaster, which means that the only thing that was needed for an early Fourth of July fireworks display that night was a sufficient catalyzing event.

So now, in the minutes leading up to the Hindenburg’s demise, a leaking lifting gas cell(s) had set the stage for an epic and spectacular disaster; therefore, the next question would be: So, what was the ignition source? Various theories as to what ignited the Hindenburg have been circulated for more than 80 years now, but the most likely explanation seems to be the presence of at least one lacerated hydrogen lifting cell in combination with the “Capacitor Spark Theory.” The Capacitor Spark Theory was postulated by professor Konstantinos Giapis of the California institute of Technology, which is commonly known as Caltech.

Image of professor Giapis courtesy of techxplore.com

As mentioned in the 2021 NOVA program about the Hindenburg Disaster on PBS, Giapis’s theory postulates that the Hindenburg’s crew dropped mooring lines during their docking sequence which were wet and thus conductive of electricity, and in turn, these wet and electrically conductive mooring lines were connected to the internal frame of the dirigible, which in turn electrically grounded all of the ship’s massive internal aluminum air frame. Official reports mention that the Hindenburg was essentially making an overly-hasty and poorly planned landing that fateful evening; that having been said, the official record also states that the Hindenburg’s crew dropped two forward mooring lines to the ground from a hovering altitude of approximately 295 feet, and this initial static electrical grounding took place at 7:21 PM.

The problem with the initial electrical grounding of the Hindenburg’s internal metal structure was the fact that the ship’s outer skin was electrically insulated from the internal aluminum structure, which in turn allowed the Hindenburg’s outer skin to accumulate a powerful static electrical charge over a time span of about four minutes. Considering the subject of a four-minute capacitor-like buildup of static electricity developing within the dirigible’s skin, it is important to remember that the fire which destroyed the Hindenburg officially started at 7:25 PM — so, this disaster started after exactly four minutes of time had elapsed past the moment when the Hindenburg’s crew first dropping their wet mooring ropes.

The figure of four minutes is significant because Giapis’s calculations place the needed time for a dangerous capacitor-like building up static electricity which would have been sufficient to create sparks that were capable of igniting the leaking hydrogen cells to be around four minutes of running time. Giapis’s theory also gains credibility because the presence of thunderstorms, lightning, strong winds, and high humidity that were present that evening would have all contributed to strong static electrical buildup on any aircraft that took to the skies over New York City and Northern New Jersey at that time.

According to Giapis’s theory, once the Hindenburg’s outer skin had accumulated enough pent-up static electricity to create a wild cascade of internal electrical sparks that would have jumped between the vessel’s outer skin and the internal aluminum superstructure, then this situation would have supplied a sufficient heat source that was hot enough to ignite whatever hydrogen was present. According to the website homex.com, the temperature range for electrical sparks varies between 1800 to 3000 degrees Fahrenheit, so yes, this capacitor-like static buildup envisioned by Giapis that jumped between the Hindenburg’s skin and the vessel’s internal aluminum superstructure would have certainly supplied an ignition source that was hot enough to set whatever hydrogen was present ablaze.

True, eyewitness reports varied a bit, but the most consistent pattern was reports that claimed the blaze broke out at the top of the vessel towards the back dorsal fin and then spread forward from there. The actual time it took for fire to consume the whole vessel varies; for example, Addison Bain from NASA speculates that the actual burn time was 16 seconds, and this figure is based on the combustion speed observed in film clips, but the official story states that the Hindenburg was consumed by flames in 37 seconds. As tested over and over again, including during an episode of the Mythbusters television show, the Hindenburg’s skin was combustible, but not truly flammable, so the rapid consumption of this huge craft by fire had to be a combination of hydrogen burning and accelerating the combustion process of the vessel’s outer skin.

Who can forget the original Mythbusters? Image courtesy of polontech.com

Competing Theories

Old Sparky and the Engine Fire Theory

The Philadelphia Inquirer ran an article on the 70th anniversary of the Hindenburg’s demise which postulated that this famous fire was started by a backfiring engine that sent a shower of sparks towards the ship’s outer skin which then set the outer covering on fire, or perhaps just ignited the already-leaking hydrogen cells, but the problem with this theory is that the outer skin of the Hindenburg was downright unlikely to go ablaze on account of a few sparks from an engine hitting it, plus the temperature of exhaust pipe sparks is just too low to ignite pure hydrogen anyway. Let us also remember that the Hindenburg’s outer skin was also wet at that time, so this theory about the blaze starting from engine exhaust sparks does not look so likely.

The Outer Skin Fire Theory

This theory was postulated by Addison Bain in 1996, and in this theory, Bain asserts that the skin of the Zeppelin caught fire due to static discharges. The problem with Bain’s theory is the fact that the Zeppelin’s skin would burn, but it would take a lot of energy to get any outer skin fire started, plus the presence of adjacent hydrogen cells would have quickly sapped whatever heat might have been present from any smoldering or burning patches of skin. Let us also keep in mind that the Zeppelin’s outer skin did collect water when humid atmospheric conditions were present, and the vessel’s outer skin also collected an awful lot of moisture whenever rainfall was present, so it would have taken a hell of a lot of energy to get the Hindenburg’s outer skin lit of fire that fateful night.

Needless to say, on the night of May 7th 1937, the Hindenburg encountered both high humidity and rain, so the outer skin of the Zeppelin would have been waterlogged and thus not very friendly to fire, plus the presence of water in the outer skin would have made the skin electrically conductive just like the wet mooring ropes were at that time; therefore, the conductivity of wet cotton canvas would have made any ignition of the outer skin by way of static sparks exceedingly unlikely. Astrophysicist Alexander J. Dessler never accepted Bain’s theory about the Hindenburg’s skin catching fire first, and Dessler’s cited reasons are that that although static sparks are hot, they do not last long enough to light the wet skin of the airship on fire by themselves, nor do static electrical sparks produce enough energy to ignite the three thick layers of polymer-coated heavy cotton canvas that made up the Hindenburg’s outer skin on their own. Dessler also notes that the insulative qualities of the doping agent that was applied to the Hindenburg’s outer layers of heavy cotton canvas would have prevented any parallel-traveling static electricity sparks from ever igniting the outer skin in the first place.

Lastly, it is important to keep in mind that Mr. Bain was a known member of the National Hydrogen Association when he forwarded his theory that it was the skin of the dirigible which caught fire, not the hydrogen itself; it just might be possible that Mr. Bain had an agenda in mind when he proposed his theory about the skin of the Hindenburg catching fire as opposed to ships lifting cells which were filled with hydrogen.

The Leaky Fuel Theory

Some people have postulated that an accidental ignition of diesel fuel within the Hindenburg’s generator room or an accidental ignition of the diesel fuel supplies that were present in one of the outer engine pods caused the disaster. The problem with this theory is that none of the witness reports mention a fire starting in the Hindenburg’s generator room nor do any witness reports make mention of any of any fire developing in the ship’s engine pods; but as stated before, the most consistent eyewitness reports recount that the Hindenburg fire began on the top-rear portion of the vessel which is far from any place where diesel fuel would have been present.

The Two Most Common Sabotage Theories

Concerning the topic of sabtage theories, it is worth noting that, Ernst Lehman, who was one of the acting captains of the Hindenburg on that airship’s last flight, believed that his ship was destroyed by sabotage until his death at a nearby medical center in New Jersey following the tradgedy. It is also worth noting that both Herman Goering, who was the supreme commender of the Luftwaffe, plus Hugo Eckner, who was then president of the Zeppelin company, along with Captian Max Pruss of the Hindenburg, all believed that the incedent was the result of sabotage at first. Max Pruss survived the incident and mantianed that the fire was caused by sabotagge until his death in 1960. Despite massive suspicions, a German committee that was created to investigate the possible reasons for the Hindenburg Fire was never able to solidly prove that this event was caused by sabotage. A more detailed rundown the the Hindenburg’s investigative committee can be found here.

The image above shows members of the German committee that was set up to investigate the underlying reasons for the Hindenburg tradgedy. Image courtesy of airships.net

Image of Captain Max Pruss courtesy of airships.net

Image of Ernst Lehman courtesy of airships.net

Image of Hugo Eckener courtesy of airships.net

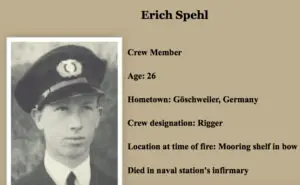

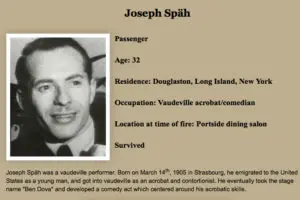

Concerning the subject of sabotage, two basic theories seem to emerge most prominently in this field. One sabotage theory postulates that an ethnically German passenger named Joseph Späh set off a bomb on the Zeppelin, and another of the most-common sabotage theories states that a crewman on the airship named Erich Spehl had planted a bomb somewhere onboard the Hindenburg, but both of these theories have their problems. For starters, Mr. Erich Spehl died in the fire; sure, maybe Spehl was just a really zealous Communist, or perhaps he was such a dedicated hater of the National Socialist Party that he was willing to give his life to bring down the Hindenburg by sabotage, but this just seems unlikely. Some people also claim that Erich Spehl’s girlfriend had communist connections and she was a dedicated opponent of Germany’s National Socialist Government, but a later deep investigation by the Gestapo proved that any hard evidence for these claims was lacking.

Image of Erich Spehl courtesy of facesofthehindenburg.blogspot.com

Image above courtesy of facesofthehindenburg.blogspot.com

As for Späh, he was an ethnic German civilian man and a passenger on the airship, Späh was also an acrobat with a history of performing in vaudeville shows, so many people think that he could have snuck around and planted a bomb somewhere on the Zeppelin prior to the scheduled arrival, but if this were true, then why would he be on board that doomed airship when the bomb detonated? Some people speculate that Späh’s plans for sabotage were compromised when the ship was delayed due to bad weather, but if that were the case, then it is likely that he would have just stopped the bomb’s timer and reset it again before leaving. True, Späh did survive the disaster, but he suffered a nasty injury to one of his ankles after he jumped out of the doomed dirigible in order to escape the fire, so having suffered a broken ankle seems to call his actions as a saboteur into question.

Image of Joseph Späh courtesy of facesofthehindenburg.blogspot.com

One big problem with any internal sabotage theory is that the Gestapo always placed at least one armed and well-trained agent on every Zeppelin flight. Each Gestapo agent who rode along on every Zeppelin flight pretended to be just another passenger, but these agents were always on the lookout for suspicious behavior. It is also worth noting that the Gestapo always sent the best they had on all of Germany’s high-profile Zeppelin flights, and this was done because both the Zeppelin company and the German government were constantly receiving boxes filled with threatening letters, and if that was not enough, both entities connected with the Hindenburg also continuously received menacing calls that were made from public telephones which were leveled against both the Hindenburg and the Graf. Threats against the Hindenburg were commonplace, and these threats began as early as the airship’s maiden voyage. Given the sheer volume of threats being made against both the Graf and the Hindenburg, the German government was in fact quite aware of the possibility that internal sabotage might happen at pretty much any time; therefore, they instituted the best countermeasures against terrorism that they could during those years.

Love the Gestapo or hate Gestapo, say what you will about them, but if nothing else they were freakishly good at nabbing spies and saboteurs. Fact is, during the really hard years of World War II, anyone who was not a true German was always eventually spotted and then executed by the Gestapo, regardless of their German language skills, and even regardless of their physical appearance, so as the (((Allied))) forces had to learn the hard way, placing internal spies within the German war apparatus was in fact impossible during the most difficult years of World War II. It is also important to remember that the Gestapo had carefully vetted each and every crewman who was aboard both the Hindenburg and the Graf Zeppelins before taking them on as members, so internal sabotage on the part of any crew member seems a bit unlikely.

Image courtesy of cartoons.com

Other factors that lend doubt to any sabotage hypothesizes include matters such as no forensic specialists ever finding any evidence of a bomb in the Hindenburg’s wreckage, and especially not towards the back portion of the craft where that fatal fire was observed to have started. True, the Jews could have arranged for any and all forensic evidence that indicated a bomb blast occuring on the Zeppelin to have been suppressed, but that seems like a bit of stretch, even for international Jewry. Yet another issue of note is the fact that the Hindenburg caught fire while the vessel was still a good distance above the ground, so any halfway-decent saboteur would probably want to at least give himself a way to exit the premises before the airship went boom.

Another factor that casts doubt on the “stashed bomb hypothesis” is the fact that the first signs of trouble appeared on the upper rear portion of the Zeppelin, whereas, it seems likely that a stashed bomb would have been most probably detonated somewhere in the passenger quarters or perhaps somewhere in the crew quarters area. Admittedly, planting a bomb in the areas where there was easy access for passengers and crew members alike seems to be a much easier task for an aspiring saboteur. Fact is, planting a bomb somewhere in the Hindenburg’s hydrogen cells area would have posed real problems for anyone who was not part of the vessel’s crew, plus entering the areas of the vessel that was filled with hydrogen lifting cells was not something that all crew members were authorized to do unless they had official reasons for moving about in that area.

True, Erich Spehl was a rigger and he did have official reasons for moving about within the vessels lifting sections, but anyone who was not part of the rigging crew that was caught sneaking around in the hydrogen lifting cell area would have certainly met with actions from the Gestapo. It turns out that even the vessel’s regular crew members would have aroused suspicion from the Gestapo if they were found moving about in areas that were not within their designated work zones. For example, if a ship’s steward was found poking around on the catwalks in the hydrogen lifting cell area, then that fellow would have some pretty serious explaining to do.

Image courtesy of marketplace.secondlife.com

The Sneaky Jews in the Woods Sabotage Theory

A less popular sabotage theory than the ones which pin blame Erich Spehl or Joseph Späh is the theory that was advocated by Hilaire Du Berrier. Mr. Du Berrier was a member of the American Office of Special Services, or OSS, during World War II, so this meant that he was involved in wartime intelligence work. Du Berrier was removed from the CIA after World War II ended because he was a bit too anti-Communist and a bit too much of an American patriot for his own good, yet he did maintain contacts within international intelligence circles until his death in 2001. Du Berrier ran his own personal intelligence newsletter out of his office in Monte Carlo from 1958 to 2001, and three later editions of his newsletter mentioned his personal contact with an American man of Irish descent name Tim McAuliffe.

Imag of Du Berrier coutesy of jamesperloff.com

According to Du Berrier, McAuliffe was a sports equipment dealer who worked for the Spaulding company and it was McAuliffe supplied the Boston Red Sox with all of the sporting equipment that they needed, so he was also a longtime contact and close associate with all members of the Redsox baseball team. What is significant about McAuliffe was the fact that he claimed to have heard the Boston Redsox catcher confess to having assembled a team of saboteurs that were equipped with a powerful sniper rifle which then went on to shoot the Hindenburg with an incendiary bullet and set the entire dirigible ablaze. The catcher for the Boston Redsox at the time of the Hindenburg Disaster was a Jewish man named Moe Berg. Berg never claimed to be present when the Hindenburg caught fire, but he did claim to have helped a group of four other radical Zionistas organize their little sabotage party.

Image of Moe Berg courtesy of jamesperloff.com

Du Berrier’s theory sound like it might be possible, but there are some problems with his story. For starters, nobody who was present that evening reported hearing a gunshot, nor did anyone who was presnet that evening report seeing a tracer round whizz through the air and strike the Zeppelin. True, the sniper rifle that supposedly burned the Hindenburg to a crisp could possibly have been fired with a suppressor attached, but there still would have been a loud noise which someone would have been likely to hear, and yes, suppressors do lessen the noise that gunshots make, but they do not eliminate the sounds of gunshots all together, and even if a suppressor is attached to a high-powered sniper rifle the sound of a round being fired is still going to be pretty damn loud.

Another problem with Du Berrier’s theory is that the Hindenburg fire is reported to have begun on the top rear portion of the airship, so hitting the top surface of a huge dirigible that is hundreds of feet in the air with a sniper rifle that is parked in the nearest grove of trees which would have still been quite some distance away seems like a bit of stretch, but I suppose stranger things have happened. Indeed, some eyewitness reports mention that the fire started on the side of the vessel near to the back horizontal tailfin, but the overwhelming number of eyewitness reports from that evening mention that the fire started on the upper back part of the vessel.

Another item to consider that casts doubt on Du Berrier’s story is the fact that during World War I, Germany operated a total of around 115 hydrogen-filled combat Zeppelins that were used for surveillance, but also for bombing. German Zeppelins are most famous for having bombed England during World War I, but the Wikipedia page about Zeppelins lists many bombings that took place around the Balkan Peninsula and the Mediterranean basin during the years of World War I. In the beginning of World War I, the Zeppelins operated above England with impunity; however, the English and everyone else for that matter, eventually found ways to down these cumbersome aircraft. An article on the website wearethemighty.com titled “Why World War I Zeppelins were harder to kill then you think” sheds some interesting light on the subject of actually killing a Zeppelin. It turns out that the British aircraft pilots who were trying to destroy German Zeppelins during World War I had a much harder time with this activity than most people would imagine, so it seems like quite a stretch to down the Hindenburg with one incendiary round this was fired from a sniper rifle.

The image above is an actual archival photograph of searchlights spotting a German Zeppelin on a bombing raid over London in 1915. The photo seen above was taken by Robert Hunt and comes courtesy of allposters.com

The image above shows a German L13 militiary Zeppelin that was used for survalence and bombing during World War I. Image courtesy of wikimedia.org

The previously mentioned article recounts that British aircraft pilots would shoot hydrogen-filled Zeppelins with incendiary rounds from machine guns like it was going out of style, yet getting the hydrogen that kept Zeppelins aloft to actually ignite was actually quite difficult and uncertain. The issue that made the prospect of downing a Zeppelin so difficult was the fact that the mixture of air and hydrogen within the lifting cells had to be fitting for the Zeppelin to catch fire at all, so most of the time burning machine gun bullets would simply penetrate the outer skin of the Zeppelins and do nothing else. A burning tracer round that was fired into a Zeppelin by a British machine gun would usually become extinguished almost immediately after it entered a Zeppelin’s hydrogen cell, and this was due to hydrogen’s tendency to remove any heat that is present quite quickly. So, in actuality, burning tracer rounds which struck a Zeppelin’s hydrogen-filled lifting cells were usually put out rather quickly, so it seems quite unlikely that a few sneaky Jews hiding in the bushes near the airfield who were armed with a single sniper rifle which supposedly only shot one incendiary round at the Hindenburg would have done much real damage.

So how did the British actually destroy the Zeppelins? The answer was that they often dropped bombs on the tops of the Zeppelins by using fixed-wing aircraft, but the British were also able to fire anti-aircraft cannons from the ground which had a ceiling of reach of about 18,500 feet, so these long-range anti-aircraft cannons were able to lacerate the hydrogen cells inside of Zeppelins with shrapnel so badly that they were unable to stay aloft. Another way that the British destroyed Zeppelins was by using machine guns that were mounted on fixed-wing aircraft to puncture the fabric of one section on a Zeppelin so many times that atmospheric air leaking into that unlucky lifting cell would eventually create an appropriately combustible mixture of air and hydrogen which would then possibly be set ablaze by one lucky incendiary machine gun round.

Interestingly, towards the end of World War I, the Germans build “High Climber” Zeppelins such as the L 48 which is pictured in the image above. High Climber Zeppelins were able to travel longer distances and operate at altitudes well above 20,000 feet. The Germans also developed and built a super-long-range high climber Zeppelin called the L65 which was designed to bomb New York City then return to Germany all while cruising at altitues well above 20,000 feet. The research done by German engineers which related to beathing at very high altitues during World War I Zeppelin rides was instrumental in the development of later underwater breating systems plus modern airplane pressurization equipment. Indeed, wartime reseach on ways to improve Zeppelins led to much better civilian craft in the 1930s. Image above and information both courtesy of sped2work.tripod.com

Interestingly, the first Zeppelins to fly over England in combat operations were very poorly armed and only stocked a single machine gun, but the Zeppelin technology did improve quickly during the war years and soon the prospect of attacking a Zeppelin in flight became a much more dangerous proposition. Attacking Zeppelins became steadily more dangerous because these craft were eventually bristling with defensive machine gun nests at every angle. Despite eventually being armed against attack from fixed-wing aircraft, the real threat to Zeppelins always came from ground-based anti-aircraft defenses, so the Germans shifted their focus to developing Zeppelins with an ever-higher ceiling of operations.

It seems quite fitting that a band composed entirely of Jews that was called The Beastie Boys released a song called Sabotage.

A Tale of Two Jews

Interestingly, a February 5, 2020 article written by Saul J. Singer titled “The Jews of The Hindenburg” appears on the Jewish Press website. Singer’s article mentions that the last flight of the Hindenburg included two wealthy Jewish businessmen. One of these Jewish businessmen was named Moritz Freibush, who was age 57 at that time. Freibush died, but it was the other Jewish passenger who was named William Lauchtenburg that survived. Freiburg was involved in importing canned fish from Scandinavia to America, and Lauchtenburg worked closely with German manufacturers of natural gas purification equipment, and Lauchtenburg was involved in the business of importing specialized German natural gas products to America. The fact that the Hindenburg was carrying two rather wealthy and prominent Jews seems to lend a bit more circumstantial evidence to the notion that the Hindenburg fire was not a case of sabotage.

Admittedly, the Jews have a terrible history of hanging their own people out to dry if they think such treachery will bring even a small benefit to their group; for example, the Pittsburg, Pennsylvania synagogue shooting of 2018 seems to be a case of Jews barbequing a few of their own to gain some public sympathy, but if two wealthy and prominent Jews were on a doomed Hindenburg flight, then it seems quite likely that someone would have given them a warning ahead of time. It also seems quite likely that the Gestapo would not have been overly suspicious if two wealthy Jewish passengers had forsaken their tickets for that doomed flight and cited their reasons for cancellation as political protest. Reports from survivors of the Hindenburg’s last trip were that the two Jewish passengers aboard the ship’s final flight did not receive a warm welcome from either the staff members or fellow passengers alike, but that should come as no surprise to anyone.

Image courtesy of knowyourmeme.com

Conclusion

The Hindenburg fire was quite a memorable historical event because it put an abrupt end to the era of massive rigid-framed dirigibles that carried passengers and mail on intercontinental flights, but the Hindenburg Fire also slammed the breaks on any further developments concerning the practice of using hydrogen-filled dirigibles as passenger transports and freight-carrying systems. Perhaps hydrogen-filled dirigibles will find their legs again in the 21st century, but the Hindenburg tragedy certainly put any serious discussion about using hydrogen-filled dirigibles on hold for many decades. Aside from putting a stop to further developments in the field of hydrogen-filled dirigibles, the Hindenburg Disaster was also possibly a portend for the dark years that were just around the corner at that time. Despite the political symbology that was tied up with the Hindenburg itself, the final demise of this awe-inspiring airship certainly made for one hell of a news story and that incident sure gifted the world with quite an amazing collection of archival photos and film clips.

Led Zeppelin artwork furnished courtesy of extrachill.com

Vintage image of the Led Zeppelin bandmembers courtesy of blog.eil.com