Japanese POW Camps and Things To Do When Your Ship Gets Torpedoed !

For the “Allied” nations to accuse the Japanese of misbehavior during World War II is hypocritical in light of what was done to the cities of Germany and Japan, but also for what was done to India concerning the Bengal Famine.

When it comes to committing atrocities, none of the “Allied” armies were model citizens; for example, the Americans would often execute surrendered Japanese soldiers by using flamethrowers.

In light of the cruelty inflicted on the Japanese soldiers by Americans, some Japanese chose to retaliate against these horrible atrocities that were committed against them. The Americans committed such terrible atrocities against the Japanese because they viewed Japanese people as intrinsically evil and not truly human. It is also important to remember that the atrocities committed by the Americans against the Japanese preceded any atrocities committed by the Japanese.

Towards the end of the World War II, both Allied POWs and their Japanese guards were starving because the “Allies” had established a food blockade on Japan. Contrary to what is popularly imagined, Japanese treatment of POWs during World War II was actually quite uneven. For example, great kindness and compassion was shown by some Japanese captors, while others were unspeakably vicious. During World War II, Korea was governed by Japan and Koreans were often conscripted into the Japanese military then assigned roles as prison guards. In many of the worst cases, it was conscripted Koreans rather than actual Japanese people who were responsible for the terrible mistreatment of captured enemy soldiers. Part of the reason that the Koreans were often the real culprits when it came to mistreatment of prisoners was because the Japanese Samurai code of Bushido actually forbids mistreatment of helpless enemies, but the Koreans had no such limitation.

Gotta love that kim-chee!!

The US and Britain provoked war with Japan to please the Jewish New World Order cabal, and this fact must never be forgotten. Concerning the Pacific theater during World War II, if it were not for the Jewish race of parasites, then nobody would have suffered and died during those awful times.

Heil Hitler deva!

Randall Lee Hilburn

The “Allies” Killed as Many of Their Own Troops as the Japanese!

The war in the Far East (December 1941-September 1945) was ferocious by all accounts, and being captured by the Japanese was no guarantee of outliving the war. Amazingly, as many Allied servicemen and women were killed by their own forces as by the Japanese.

Between the 12th and the 18th of September in 1944, Allied forces sank three Japanese vessels that were carrying supplies to support the Japanese war effort; however, the “Allies” were unaware that these ships were also carrying “Allied” prisoners of war (POWs) and Javanese slave laborers called (Romushas).

The “Allies” also sank plenty of other enemy vessels during September of 1944 that were carrying war supplies and slave laborers. Eyewitness testimonies from rescued passengers who survived the sinkings of the Japanese ships named Kachidoki Maru and Rakuyo Maru on September 12 1944 supplied the “Allied” command with their first reports about conditions in forced labor camps along the Thailand-Burma railway. Additionally, the sinking of the ship named Junyo Maru on September 18, 1944 was one of the deadliest maritime disasters of the Second World War. The combined sinkings of Japanese ships from that September resulted in the deaths of over 7,000 “Allied” servicemen and women.

The Kachidoki Maru was the largest of the Japanese vessels sunk by the “Allies” that September, and this vessel had a registered gross tonnage of 10,000 and a length of over 500 feet. The Kachidoki Maru was torpedoed, along with the Rakuyo Maru on 12 September 1944, and these attacks were carried out by American submarines while the Japanese ships were traveling to mainland Japan by way of Singapore.

The Junyo Maru was the smallest of the Japanese ships that was sunk in September of 1942 with a length of 400 feet and a registered weight of 5,000 tons. The Janyo Maru was torpedoed and sunk by a British submarine on the 18th of September, and this attack happened off the western coast of Sumatra. When these Japanese vessels were sunk, the “Allied” POWs and slave laborers on board were either returning from work on a railway project, in transit to mainland Japan, or journeying to a different railway project where they had been previously assigned to work.

More than 1,300 Western POWs were packed on board the Rakuyo Maru, and a further 900 were packed into the Kachidoki Maru at the docks at Keppel Harbor in Singapore on September 6, 1944. These “Allied” captives of the Japanese who were leaving Singapore and were soon to meet a bad fate at sea had labored on the Thailand-Burma railway which was a 250-mile long construction project where these unfortunate prisoners had been forced to work since June of 1942.

The photo above shows POWs building the Thailand-Burma rail line.

Just for the record, approximately 100,000 Romushas, 12,000 “Allied” servicemen, along with women, and civilians of all types also lost their lives as a result of the brutal forced labor conditions along the Japanese Thailand-Burma rail-line project.

Although the main construction work on the Thailand-Burma railway had been completed by October 1943, the men who labored on this project were still suffering from the effects of severe malnutrition and tropical diseases such as malaria, dysentery, and beriberi when they boarded the doomed Japanese ships. In their conditions of sickness, the slave laborers who were being transported from Singapore to jobs elsewhere were crammed into the holds of Japanese ships with the hatches closed. Eyewitnesses described this awful situation as “a layer of men lying shoulder to shoulder,” and one such witness was an Australian private named Philip Beilby. Within his transport ship, Beilby described men laying on shelves in the hold that had shelves filled full of other men that rested just a little bit above each subsequent layer. Beilby also described the prisoners being forced to use rudimentary toilet facilities that were simply wooden boxes with holes cut in their bottoms that were suspended over the side of a ship deck.

The Rakuyo Maru and Kachidoki Maru set sail on September 6 from Singapore to Japan as part of convoy that was given the code name HI-72. As well as transporting war captives, these ships were carrying supplies for the Japanese war effort that included oil, rubber, and bauxite. The critical materials that these Japanese transport ships were carrying along with Japanese soldiers certainly made these convoys that were leaving Singapore attractive targets for “Allied” attacks.

As the transport vessels left Singapore, Japanese troops and “Allied” captives alike were unsure if their ships would make the journey to Japan safely. Everyone on those ships had good reason to worry as they left Singapore because earlier that September other Japanese transport ships had already been lost to “Allied” attacks including the Lisbon Maru on the 1st of October 1942, the Suez Maru on the 29th of November 1943, the Harugiku Maru on the 26th of June 1944, and the Koshu Maru on the 4th of August 1944. In total, 23 Japanese ships that were transporting prisoners of war are thought to have been sunk by “Allied” forces during the conflict in the Far East. The death toll from these sinkings is estimated to include 11,000 POWs. Additionally, the Romusha death tolls are unknown, yet the estimates for Romusha deaths are in the tens of thousands.

Upon boarding the Rakuyo Maru, some Australian POWs drew upon their experiences surviving the HMAS Perth’s sinking that happened during the Battle of Sunda Strait which took place at the end of February 1942. As the Australian POWS were packed into the holds of their assigned transport ships, they gave advice to their fellow POWs concerning what to do in the event of a sinking.

While in transit, the men who were confined to the ship holds would talk amongst themselves and ponder which type of work they might be assigned upon arrival in Japan. The rumor was that the POWs would be assigned the harsh duty of coal mining after they arrived in Japan, yet nobody on board had any prior experience working as coal miners. The prisoners suspected that they would be put to work as coal miners because this type of work was critical for industrial functions in the 1940s, and it still is today. Coal mining was of such a high priority to any wartime economy that coal miners were exempt from serving in the armed forces during World War II in Britain.

The “Allied” POWs and forced laborers from Southeast Asia who were crammed onto the Japanese transport ships did not have much in the way of mementoes, clothing, or any other possessions for that matter, and during their previous two years of captivity they had all become physically acclimated to weather conditions that were very different from they would soon encounter in Japan. The men confined to the Japanese ships had grown accustomed to tropical heat in Thailand, and now they were heading to a temperate climate with freezing winters, so they were all quite concerned about how well they would adjust to hard physical labor in snowy conditions. The men confined to the holds of these Japanese transport ships were also concerned because they did not possess any cold weather work clothes themselves, and they were unsure if any suitable cold-weather clothing would be provided.

Any amount of time that these prisoners of war were allowed out of the hold onto the decks was precious because each man was given a chance to breathe some fresh air instead of just breathing the stifling stink of the dysentery-ridden hold. The allotted times on a deck during the voyages also permitted each man to finally move his stiff and cramped limbs.

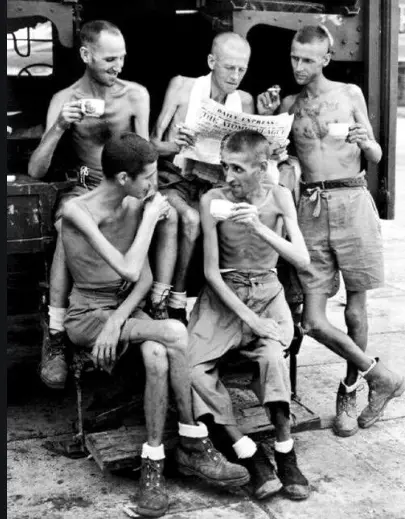

The photo above is an American Army photograph that shows Western POWs of unknown nationalities who were laboring on the Thailand-Burma rail line.

At 5.00 AM on September 12, six days into the voyage, torpedoes from USS Sea Lion struck the Rakuyo Maru, and at this time, rivers of fire were still blazing in the sea from the convoy’s oil tankers that had been hit by torpedoes earlier that night.

The men who were confined to the Rakuyo Maru knew that they needed to abandon ship after it was struck by American torpedoes, yet there were very few lifejackets from the start and the Japanese had already appropriated all of the lifeboats by the time the laborers reached the ship’s upper decks. Given the lack of lifeboats and life preservers, the allied prisoners of war who were aboard that doomed ship simply threw anything in the water that might float, which included pieces of wood and anything they could find that was made of rubber. The prisoners who were abandoning the sinking ship also remembered to collect as many bottles that they could find before they jumped onto their makeshift life rafts. As many bottles and containers as possible were included in these hasty departures because having any way to store rainwater at all would be crucial for survival later on.

The crude oil in the surrounding seas caused the escaping men to retch as they accidentally ingested it, and contact with this floating crude oil burned the skin as well. The crude oil burned the skin when it made contact, but so did the saltwater, and to make matters worse, most of the prisoners had open and infected ulcers somewhere on their skin. However, despite irritating the skin, these coatings of crude oil also created a thick greasy layer that offered some protection from the harsh sun during the day and the bitter wind at night. Survivors of the initial attack simply remained in the vicinity of the broken ship hoping for a rescue, yet they also kept some distance from the waterlogged ship to avoid being pulled under the ocean when the Rakuyo Maru finally went to the bottom of sea.

At 10.40 PM on September 12, the USS Pampanito torpedoed the Kachidoki Maru. The Kachidoki Maru sank much quicker than the Rakuyo Maru, and this doomed vessel went to the bottom of the ocean within minutes rather than hours, and the 900 men on board that ship had to jump into the sea during the night with little time for planning.

During this sinking, the stronger swimmers tried to help those that they could hear struggling around them. “But”, remembered Thomas Pounder, who was a gunner with the Royal Artillery, despite his confidence in the water, he recounts, “when I hit the water, I went right down. It seemed as though somebody wrapped a rug right around me, I couldn’t move.” Having struggled to reach the surface and having been pushed away from a lifeboat by Japanese guards, Pounder eventually managed to climb onto a bamboo raft where he would spend the rest of the night. As day broke, Pounder looked for the man who had been his best friend throughout their time on the Thailand-Burma railway. Pounder’s friend had not only worked on the Thailand-Burma railway with him, but this man had also been next to him on the ship. However, these two close friends had been separated during the sinking and the Pounder’s friend was eventually counted among the 400 men who lost their lives during the sinking of the Kachidoki Maru.

Other Japanese ships returned the following morning to pick up the surviving men along with over 500 other POWs. After his rescue, Pounder was transferred to the Kibitsu Maru, where he continued his journey to mainland Japan and remained there until the war’s end.

By contrast, for the survivors of the Rakuyo Maru, the wait time for a rescue stretched to three, four, and even six days. Ironically some of the survivors from the Rakuyo Maru’s sinking were rescued from the sea by the same “Allied” submarines that had attacked that ship earlier.

For the survivors that spent day at sea awaiting a rescue boat, a survivor recounts that the men became “absolutely famished for water, the mouth dries up and your tongue sticks to the roof of your mouth, yet all the while staring out at pure and crystalline-looking saltwater.”

For the first couple of days, the men who survived the sinking tried to maintain their morale by singing songs to pass the time, but the sun’s glare off the water eventually became “unbearable,” the oil in the eyes burned, the saltwater ulcers caused “itchy patches,” and the skin peeled away in some spots.

Hallucinations induced by heatstroke, dehydration, and trauma caused some men to leave their rickety life rafts and try to swim out to ships that were not there, and many drownings resulted from these wishful hallucinations. Many men died of thirst, some became very aggressive, and others simply went crazy. The men had jumped from the Rakuyo Maru feeling free because their captors and their bayonets were no longer around; however, one survivor noted, “but you’re not free really because the bottom of the sea is calling you.”

Luckily, the USS Pampanito and USS Sealion had continued to patrol the area in the South China Sea following the attack on the Japanese convoy, and after three days, American submarine crews spotted wreckage and debris floating in the water with men perched on top.

When encountering the survivors from the Rakuyo Maru, “We couldn’t recognize them” reported Lieutenant Commander Davis, who was the Executive Officer on the Pampanito, “They were all hollering and screaming at the top of their voices. They were very hard to handle, they were just covered with a heavy oil, all over their bodies, their hands, and we had a devil of a time trying to get them on board, they were slick, couldn’t pick them up. They were quite weak and they couldn’t help themselves very much. I remember the first one that came up, he actually kissed the man as he pulled him up on deck, he was so happy to get on there.”

“They were quite in a state of hysteria; they had practically given up when they finally got picked up by us.” Lieutenant Commander Landon Davis’s full account of rescue is available on the San Francisco Maritime National Park Association’s website, as is remarkable edited film footage of the rescue of 157 POWs from the Rakuyo Maru sinking. The film that shows the desperate POWs getting rescued by an American submarine was made by using the USS Pampanito’s periscope cameras, and this original film footage is still preserved within US National Archives.

A typhoon hampered American rescue efforts in the day following the ship sinkings, but for three days the submarines, with assistance from USS Barb and USS Queenfish, continued to rescue survivors. A small number would die in the days following their rescue, but the overwhelming majority of the surviving war captives from the Rakuyo Maru were eventually repatriated to Australia and Britain.

Whilst onboard the submarines, the former POWs heard the news of the war’s progress, and they provided their own intelligence to military personnel concerning conditions in the Far East. The Western POWs who were rescued by American submarines offered lavish praise for the submarine crews, and they were quite grateful for the medical care they received in Saipan.

At 4.15 pm on September 18, 1944, which was the same day that the last of the men from the Rakuyo Maru were being pulled from the sea, the Junyo Maru also got torpedoed off the western coast of Sumatra by the British submarine named HMSM Tradewind.

Conditions on board the Junyo Maru were as cramped and degrading for Allied POWs as they were on other transport ships; however, the Junyo Maru carried 4,200 Romushas who had also been beaten with clubs and forced down into the holds by guards who were intent on cramming as many people as possible into the space available. It is worth noting that Romushas suffered particularly inhumane conditions for the entire times of their detentions. It should come as no great surprise that the Romushas were treated with notable disregard by the Japanese during the war years because the Japanese has a certain respect for European culture and its achievements, whereas the same could never be said for the native people of Java. To the Japanese, White men deserved at least some respect on account of the achievements of their culture, such as inventing aircraft and electricity, but the Romushas were simply seen as expendable coolie slave laborers. Few Romushas are reported to have made any attempt to leave the stricken ship, and only 200 are thought to have survived the sinking because they chose to huddle together on board rather than jump off the ship and take their chances out on the water.

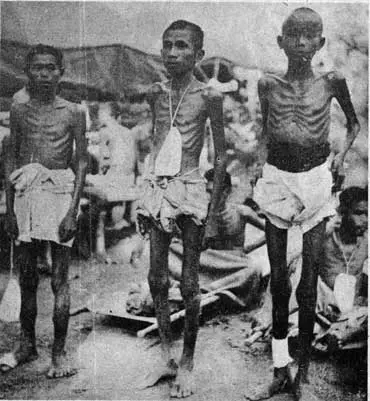

An old archival photo of Romusha railway workers on the island of Sumatra.

Former POWs spotted in the South China Sea by USS Pampanito following the sinking of the convoy including the Rakuyo Maru and the Kachidoki Maru in September 1944. The men seen in the above photo were rescued by the same US submarines responsible for the sinking.

The sinking of the Junyo Maru was one of the deadliest maritime disasters of World War II, and one of the worst maritime disasters in history at that time. It took less than one hour for the vessel to sink into the Indian Ocean, and more than 5,500 lives were lost in this incident. After this sinking, the 880 survivors, like those on the Kachidoki Maru, were picked up by Japanese ships and put back into forced labor on another railway that was constructed under the command of the Japanese Imperial Army. These forced laborers were specifically sent to build the Pakanbaroe railway that crossed the island of Sumatra.

The above photos shows survivors from the convoy containing the Rakuyo Maru and Kachidoki Maru, being rescued from the South China Sea by the crew of the USS Pampanito on 15 September 1944.

Like at the Thailand-Burma railway project, POWs and Romushas were forced to build the Pakanbaroe railway through thick jungle, swampland, over rivers, and across mountain ranges. The slave laborers who built these rail lines were forced to use basic hand tools and they survived on a meagre diet of rice, jungle vegetables, and scraps of meat — when any food was available at all.

The survivors of the Junyo Maru shipwreck were transported to a Japanese base camp at Pakanbaroe, which was one of 17 camps along the intended new rail line. From there, these forlorn laborers were moved in groups along the rail line where they joined nearly 5,000 other “Allied” POWs who were working grueling shifts to construct the tracks and bridges for the cross-island Japanese rail line, as well as laboring to build the camps that they needed to inhabit as their work progressed. These conscripted laborers would continue to work until the railway was completed 11 months later, which just happened to be the same day as the Japanese surrender, August 15, 1945. During the construction of the Pakanbaroe railway, 673 Allied POWs and 80,000 Romushas lost their lives.

Former Allied POWs being rescued from the South China by USS Pampanito following the sinking of the Rakuyo Maru and the Kachidoki Maru. The men who survived the sinking were eventually repatriated to Australia and Britain and their stories provided the first personal accounts of conditions along the Thailand-Burma railway.

Whilst the surviving men from the Kachidoki Maru labored in Japan, and those from the Junyo Maru built the Pakanbaroe railway, the men who were rescued and repatriated after surviving the “Allied” attack on the Rakuyo Maru provided Australian and British officials with direct evidence of their experiences in captivity. The testimonies furnished by rescued POWs were the first accounts given to “Allied” administrations and the general public that described the conditions endured by the POWs who were forced to work on what came to be known as the “Death Railway.”

On 17 November 1944, as details of the Thailand-Burma railway were making their way into the British press, and Britain’s Secretary of State for War at that time was a man named Sir James Grigg. It was Grigg who made a statement in the House of Commons that was based on the accounts given by survivors from the Rakuyo Maru.

In his parliamentary speech, Grigg directly addressed the situation of POWs being held in the Far East. During Grigg’s speech before Parliament, a commendation was specifically given to medical personnel on the Thailand-Burma railway project for looking after sick and injured men with very little medicine or equipment.

After World War II, Britain’s Department of the Red Cross and St. John War Organization produced The Prisoner of War, which was a journal for the relatives of men who were held captive by enemy troops during the Second World War. From February 1944, this journal was supplemented by a special eight-page edition called Far East which enabled information to be distributed more efficiently to the relevant families.

In March 1945, one of the survivors of the Rakuyo Maru wrote a double-page spread for Far East that attempted to appease the concerns of families.

“I know by the way I felt during my two and half years that our greatest wish was for you not to worry.” The man who wrote the two-page spread for Far East said that he wrote his articles to give families of the Japanese POW camps “an idea of what our daily lives were like,” and he wrote of the work, the punishments, and the lack of food. He also explained that there was no chance for anybody to escape these POW camps, and once you were caught trying to escape, “you didn’t get another chance.”

In writing to families about the daily lives of the POWs, the article that appeared in Far East additionally mentioned that the men who were returning from the Rakuyo Maru were unaware that their comrades across the Far East were still suffering under forced labor conditions and enslavement along Japanese railways and their brothers at arms were still being forced to work in coal mines.

Source: Michael Walsh