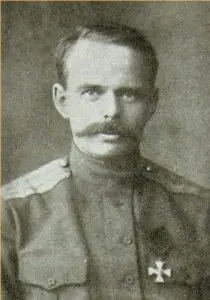

What Lessons Does the Life of Baron Roman Ungern-Sternberg Have to Offer?

UNRAVELLING THE LIFE OF BARON ROMAN VON UNGERN- STERNBERG

by Martin T.

Understandably enough, the life history and adventures of Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg has generated little favorable interest across the West in recent decades because we live in an epoch where an anti-Bolshevik and anti-Semite such as Ungern-Sternberg will not receive a warm reception. Historians, if not “History” itself, has rendered its collective verdict against the Baron: he is nothing more than a berserker and a historical bit-player who rode alongside the bigger villains of the Russian Revolution such as Kolchak, Semenov, and Wrangel. (1)

James Palmer’s book titled “The Bloody White Baron” (Basic Books, 2008). Offers a slightly ironic and mostly bemused treatment of Ungern-Sternberg that typecasts him as nothing more than a stereotypical Russian nobleman, which means that he was portrayed as a temperamental sadist with assorted esoteric preoccupations that provided his tottering and unstable psyche with a badly needed set of crutches.

Dr. Richard Spence’s book titled “The Bloody Baron von Ungern-Sternberg” (www.newdawnmagazine.com) is quite insightful in many of its pronouncements about Ungern-Sternberg, yet Spence’s treatment of the baron is vitiated by the author’s evident distaste for the Baron’s anti-modernist thinking which strikes Spence as “weird.” In cases such as Spence’s prognosis of the baron, one is reminded of a notable public quire made by Jerry Seinfeld’s mother: how could anyone NOT love Jerry? It seems that Seinfeld’s mother is also saying by proxy: how could anyone not love modernity?

Such attitudes about modernity and post-modernity such as Spence’s are more to be expected than deplored in our times because w are living in the Kali Yuga, and after all, the Kali Yuga will go on decaying unit final turn of the screw, yet we have not yet arrived at the screw’s final turn. That being said, as recently as several decades ago the collective scholarly assessment of the Baron was quite different than it is today. Until somewhat recently, the baron was not seen as a sadist and a sorcerer, which exemplified by Keyserling declared him, “The most remarkable man I have ever had the good fortune to meet, his nature suspended in the void between heaven and hell.” Julius Evola wrote about the baron in a similar vein: “…only the sacred force above life and death animated him.” Berndt Krauthof also penned a well-reviewed biography of the baron titled, “Ich Befehle” (available in English as “Strife and Glory,” Vantage Press). Rene Guenon’s 1938 book titled “Etudes Tradtionelles” also carried a largely laudatory treatment of the Baron’s failed political program.

Warm biographical receptions for Baron Ungern-Sternburg were by no means confined to Europe. In Mongolia, the more traditional Buddhists still consider the baron to be the “Tenth Avatar,” who is variously described as either a devine avenger or a fierce judge. Likewise, the thirteenth Dalai Lama officially declared Ungern-Sternberg to be an avatar of the Dharmapala (guardian deity) Mahlakala.

Lastly, to bring this matter full circle, in our own time Alexander Dugin published a judicious but largely favorable treatment of Ungern-Sternburg titled “Baron Ungern: God of War (www.eurasianist-archive.com). It is worthy of special note that Dugin placed the Baron’s spiritual concerns well before his political program or his personal failings. Still, Dugin’s piece represents an outlier’s position concerning a subject that most Westerners will even hear about, much less entertain.

So, after a brief summary of the literature surrounding the baron Unger-Sternburg, the question arises: why should we care about a character who was only a briefly popular figure within small right-wing circles during your great grandfather’s day? The answer is simple: to assess any man, first take a good look at his ememies. In a 1920 letter to Lenin, Feliks Dzerzhinsky, who was the first head of the Cheka, wrote the following: “Ungern-Sternberg’s monarchial plans are limitless…One thing is clear: he is preparing a blow. He is our most dangerous enemy to date. Destroying him is a matter of life and death.”

Judging by his enemies, the life of Ungern-Sternburg still holds relevance for our time because Bolshevism remains to this day. True, Bolshevism has altered its appearance and assumed the shape of today’s “cultural Marxism;” none the less, the impetus of Bolshevism remains the same. In light of Blolshevism’s present resurgence and troubling success, the White Baron’s life holds some lessons for this of us who are “bleiben doch treu” to Tradition. Therefore, we will consider the implications of the baron’s doings and spirituality, then analyze how he faced defeat.

Unfortunately, Ungern-Sternberg WAS undeniably a very cruel man. Modernism and Post-modernism know of no other way to wrap their collective minds around Ungern-Sternburg’s well-known streak of cruelty besides just declaring him a “sadists.” Labeling Ungern-Sternburg a “sadist” in good Semitic fashion has the drawback of compacting this mystical man and his difficult-to-fathom motives down to simple a simple impulse. Let us state a blunt fact: cruelty is only one tool consider among others when dealing with dangerous or recalcitrant people. If cruelty is a tool, then cruelty is one tool that the baron had no scruples about using. The question of whether or not Ungern-Sternburg is an “admirable”person is really an intellectual red-herring. therefore, we should never bother to ask this question. The right question to ask about Ungern-Sternburg is whether he was a leader who deserved loyalty under HIS particular circumstances.

Part II.

Although the Baron was a staunch and lifelong czarist, he was actually of German ancestry. The baron was born in his mother’s native Graz in 1885, and grew up mainly on his Baltic German father’s estates in what is presently called Estonia. His father’s branch of the family could trace its ancestry back to the Teutonic Knights of the High Middle Ages and the baron boasted that no fewer than seventy-two of his ancestors had fallen in that region’s various wars.

Thus, young Roman Ungern-Sternberg was groomed for a military career in the Russian Imperial forces during his childhood. However, any plans for a long and notable career within the Russian Imperial Military were derailed at the outset when Podchinenny (Subaltern) Ungern-Sternberg was cashiered from his Cossack regiment for dueling in 1910. This dueling incident not only left the baron with blighted prospects, but the same incident also earned him a serious saber wound to the head, so young Ungern-Sternberg’s dueling escapade amounted to an all-around bad bargain. (As well as providing armchair materialists with a physical “explanation” for this man’s later fierce behavior.)

Separated from military service in Chita, which is near the junctions of Russia’s Far East, Mongolia, and China proper, young Roman undertook an odyssey of the region accompanied only by his wolfhound Misha. As chance — or kismet — would have it, the baron was in the Mongolian capital at the outbreak of the 1911 “bourgeoisie revolution” in China. In the chaos of those times, the Buddhist leader of the Mongols, who was known as Kutuktu Bogdo, sought to expel the Chinese because at that time Mongolia was a suzerain to the much larger nation of China. As a foreign-trained cavalry officer, Ungern-Sternberg found his services in high demand. Performing with some tactical brilliance and his trademark daring, the young Ungern-Sternberg found himself earning the Kutuktu’s personal esteem. It was at this time that one of the local shaman styled the bellicose Russian officer as the “Tsagan Burkhan,” which translates to English as — White God of War — which foreshadowed a brilliant, but brief, military career in Mongolia.

After this Mongolian backwater brushfire of a war concluded, Ungern-Sternberg returned to Europe. For the next two years — 1912-1914 — the baron passed his time in Austria-Hungary, Germany, and especially France. There, according to Krauthof, he met a young woman named Danielle who was the love of his life. Krauthof’s tale goes on to relate that while young Roman was returning to Russia in hopes of rejoining the Russian army and fighting in World War I late in the summer 1914, Danielle drowned in a boating mishap on the stormy Baltic Sea.

This tale smacks of fiction because Danielle’s persona is denuded of everything except a first name and other authors such as Palmer never mention this matter. On the other hand, both Dugin and Evola see this mishap one of the pivotal points in the Baron’s life. As the latter has it, “This great passion incinerated all human elements inside him. From then on, only the sacred force above life and death animated him.” Whatever the cause, it remains a fact that acquaintances noted a marked asceticism and cruelty in the still-young officer from this point forward.

In the upcoming war, such qualities as asceticism and cruelty were cherished traits with a handsome premium. During World War I, the Baron was wounded five times and decorated with the St. George Cross, which is a medal awarded for “undaunted personal courage.” The end of World War I found the Baron on the Persian Front, but he he did not remain at loose ends for long because the end of World War I marked the beginning Russia’s civil war against the Bolsheviks.

As early as 1915, the Baron attracted the notice of Ataman Grigori Semenov who was a Cossack-Buryat officer of no small ability and élan. When the outbreak of fighting against the Bolsheviks c0mmencecd, this dynamic duo began recruiting new soldiers in the Urmia area (present-day Azerbaijan.) With the deterioration of the military situation in the Urmia region during the later part of 1917, Sternberg and Semenov made their way to Manzhouli, which sits on the Chinese/Russian frontier. Manzhouli was Semenov’s native land, and this was also a place where Ungern-Sternberg was already a known and respected personage.

In Manzhouli, these two notable personalities raised and equipped an Asian Cavalry Division, which was made up of Russian and Cossack officers who were leading Buryat rank-and-file soldiers. (2) Here, the military situation was chaotic due to poor communications that arose from vast and largely empty expanses of land which made coordinating operations difficult. Although the Asian Division was nominally subordinated to Admiral Kolchak, Ungern-Sternberg’s force largely operated as an independent command. Likewise, Semenov’s propensity to sensual dissipation rendered him an increasingly “hands off” type of commander (read, “absentee”); thus, Ungern-Sternberg became the de facto leader of the Asian division.

With Kolchak’s defeat and capture in early 1920, Ungern-Sternburg’s situation took a turn for the worse. Though Semenov claimed suzerainty of the Trans-Baikal region, Bolshevik military gains along with the Ataman’s withdrawal deeper into Manchuria rendered this claim hollow. A nadir was reached with the Kutuktu’s capture by Chinese troops who were operating under Bolshevik direction.

It was during these dark times that Ungern-Sternberg’s career reached its pinnacle. Acting on his own initiative, Ungern-Sternburg launched a guerrilla raid that freed the Kutuktu, followed by a massive assault by his mounted troops that freed Mongolia’s capital. The grateful Mongolian leader named the Baron “Khan of War,” which make him effectively Mongolia’s warlord.

And it was there in Mongolia at this same time that Ungern-Sternberg began his precipitous decline. At this time, Ungern-Sternberg proclaiming his intention to found a religio-military order based on Teutonic Knights and the Knights Templars. In this new order, the Baron imposed a fanatical degree of discipline on his forces. For example, a bevy of officers who were caught drinking were thrown into an icy river and ordered to swim to the far side, and fewer than half of these eighteen officers managed to complete their swim. A gifted Cossack cavalry commander was also executed for abusing a stray dog, and this death sentence was carried out because such actions violated the Baron’s strident interpretation of Buddhism.

While many of the excesses observed in Mongolia might be (and have been) blamed on Colonel Sipailov, who was known to be the Baron’s eminence grise; none the less, the fact remains that Ungern-Sternberg did nothing to check his underling during this incidence. As the largely sympathetic Dugin concludes, “All the means by which Ungern imposed order in Mongolia resembled Bolshevik terror.” Paradoxically, or rather understandably, reports of these excesses only increased the Reds’ respect for the Baron.

By 1921, the anti-Bolshevik cause was collapsing. In the West of Russia, Wrangel fled the fight via the Crimea peninsula. During these times, Czechs in the Irkutsk region also betrayed Kolchak during the previous year and the Whites’ most prominent leader was also executed. Closer to home, Semenov finally cut his ties with the Asian Division and sought to establish himself as a Japanese tool in Korea, and only Ungern’s Asian Division represented a force in the field. Informed of these developments, a subordinate to the Baron declared, “This is a catastrophe.” To which Roman replied, “No. It is an honor.”

During these bad times, the Kutuktu himself decided to flee to China. It is said that, in parting, the Katuka gifted Ungern with a ruby ring incised with a Swastika. The ring, he informed the War Khan, was worn by none other than Genghis Khan himself, and Kutuktu adjured Ungern-Sternberg never to remove this ring.

Image courtesy of jakejohns on beta.cent.co

At this point, with the Bolsheviks were closing in on Ungern-Sternberg from at least three sides, the baron resolved to fight back with a bold stroke. Ungern-Sternburg’s plan was to rally the shattered White forces in western Mongolia, then to strike south across Xinjiang and establish himself in Tibet. To his wavering troops, the plan seemed like pure madness; thus, in August of 1921, the Baron’s Russian and Cossack contingents mutinied and Ungern-Sternberg was forced to flee with the small compliment of Buryat troops who remained loyal.

After fleeing, Ungern-Sternburg’s end came quickly. Within a few days, he was captured by Bolshevik cavalry units operating in the area under unclear circumstances, and the baron’s more disapproving biographers tend to insist that he was “betrayed by his own men.” Yet, Dugin, and even the lukewarm Palmer, both assert that Ungern-Sternburg was surrounded by a small body of loyal, albeit vastly outgunned, troops.

Whatever the facts, the outcome was a foregone conclusion. After refusing an offer to renounce his beliefs and join the Bolsheviks, Ungern-Sternberg was given the expected show trial, then condemned to death. His captors’ accounts all agree that Ungern-Sternberg walked to his appointment with the Bolshevik firing squad in the manner of a man who was excusing himself to leave the room for a few moments.

Part III.

Today, so much of Baron’s life remains mute, yet when the details of his life are suffused with the ideas that animated them they speak with a fiery voice.

Understandably, Ungern-Sternburg was a man of action, so he wrote very little. Most of what is actually known about the baron’s thinking comes from quotations of what he said to others. Or, rather, what he is rumored to have said, yet such sources as these have varying degrees of reliability. One of the few extant scraps that actually came from the Baron’s pen is his Order #15. This short piece of writing offers a window into the baron’s mind because it is emblematic of the man and the thoughts that infused his mundane goals with a profound spiritual significance.

Most trenchantly, the objective of restoring the Romanovs to power was cast as a prominent part of the baron’s designs: “extirpate at its root the evil (Bolshevism) which has come to earth to destroy the divine in man.” Indeed, the very title of this document is significant. Whatever his erratic tactical brilliance might have been, Ungern-Sternberg was never a particularly organized commander who relied on meticulous staff work. Put plainly, there exists no Orders #1-14. Rather the number 15 was chosen by the Baron’s conclave of attendant shaman simply because it was numerologicaly propitious. For Ungern-Sternberg, his mission was conceived in the fashion of a caduceus. A caduceus is a symbol that featured two serpents intertwined with one another, and in this case, the duel serpents were politics and esoteric spirituality.

If we wish to access a more explicit presentation of Ungern-Sternberg’s political agenda, it is to his subordinates to whom we must turn. In a 1938 article that appeared in Guenon’s journal “Etudes Traditionelles,” an erstwhile Major who served in the Asian Division named Antoni Aleksandrowicz, published Ungern-Sternberg’s program as the Major understood it. The eight points of Ungern-Sternburg’s program are:

- The Bolsheviks are to be warred upon as the enemies of civilization.

- The bulk of Russians are to be despised for betraying their Emperor.

- The intelligentsia are to be hated for spearheading both items #1 and #2.

- A knightly order is to be established along the lines of the Teutonic Knights and this order is to incorporate the tenets of Bushido.

- A coalition of reliable Russians and Asiatic troops are to be led by this Order with the goal of extirpating the Bolsheviks.

- Contact with the Dalai Lama will be maintained to inform and maintain the Order’s spirituality.

- Admitting pain, joy, pity, or sorrow all detract from the Order’s mission.

- Psychic tendencies are to be cultivated by those with the aptitude. (Antoni, as many others, noted the Baron’s oftentimes unsettling propensities in this direction.)

The Bolsheviks were not the only foe against to which Ungern set his attention, merely the most evident. Ungern-Sternberg opposed Jewish capitalists as, “an omnipresent, often undetected, enemy.” (3) With this awareness of Jews, the baron did not see Bolshevism in the same manner as most contemporary Western historians. Most contemporary Western historians view Bolshevism as a regrettable but understandable response to structural inequities and the Great War’s disruption. By contrast, to Ungern-Sternberg, the Red Creed represented one more head of a very old Hydra; namely, the Jews. In a terse exchange with his Jewish/Bolshevik prosecutor during his final trial, the baron declared, “Communism originated nearly 3000 years ago during the Jews’ captivity in Babylon!”

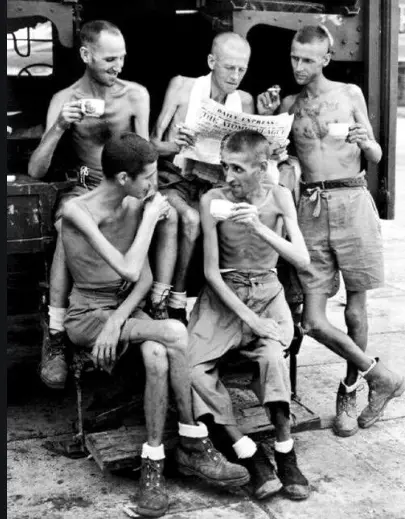

Image courtesy of yadvashem.org

The Baron planned to set up a shield against the menace of Jewish Bolshevism by using Mongolia itself as a shield. By happy synchronicity, Mongolia’s native name — “Khalka” — means “shield” in the local language. Ungern-Sternberg’s planned Russo-Mongol anti-Bolshevik coalition was slated to first shield the world against the “Gog and Magog” of Bolshevism and capitalist/democracy. Although he was separated from the Traditionalists in Europe, the baron recognized that the twin ideological strains of Bolshevism and Capitalism both arose from a common and perverting Jewish root. Ungern-Sternberg’s plan was never simply a defensive measure along the lines of today’s “white flight” in the United States. Rather, Ungern-Sternberg envisioned that Khalka would serve as a springboard for an attack on the West: “From this magical point of sacred geography shall begin the Great Restoration.”

Turning rhapsical, even as the military situation deteriorated, Ungern-Sternberg dreamed of a day when, “We will speak Sanskrit and live according to the Rig Veda. We shall regain the law that Europe has lost. Once again, the light of the North will shine. The eternal law, dissolved in the waters of the Ganges and Mediterranean, will prevail.” ( This sounds a bit like the Thule Society’s dreams.)

Image courtesy of epal.gg

With ideas such as these, Ungern-Sternberg was skating the line between political objectives and religious fervor. Interestingly, some of Ungern-Sternberg’s more astute enemies have noted that it was by religion not psycho-sexual sadism that the Baron is to be understood. A 2016 article in (((The Atlantic))) went so far as to declare that Ungern-Sternberg was a staunch anti-Bolshevik who represents a “precursor to ISIS.” (4) (And surely this remark says at least as much about the intellectual underpinnings of the woke West as it does Roman von Ungern-Sternberg himself! The author of this Atlantic article seems unaware of the fact that his offered parallel analogy actually peggs today’s globalist West as a successor to Bolshevism. Or perhaps this same author is tacitly proud of this fact.)

As hinted above, it is always a mistake to delimitate politics and spirituality because these two forces always intertwine like the twin serpents of a caduceus. Since man acts as a whole, politics and religion will always overlap and only those who are too weak for either pursuit will seek to separate the agora and naos into sealed and separate spheres. As The Führer stated about a decade after Ungern-Sternberg’s death, “Who sees in National Socialism only a political party has understood nothing. We aim to restore the god-like in man.” Ungern-Sternberg might well have agreed with the The Führer statement on this matter. Certainly, Ungern-Sternberg implied as much about his own agenda.

Part IV.

It is somewhat difficult to nail down exactly when Ungern-Sternberg became a Buddhist. In a late conversation with the Polish adventurer Ferdinand Ossidowski, the baron insisted that his paternal grandfather embraced the Dharma during a sojourn in India, as did the baron’s father.

On the face of it, Ungern-Sternberg’s interest in Buddhism is mildly problematic because The Dharma is said to have vanished from India long ago in the face of Hindu indifference and Mogul persecution. Such a Buddhist revival in India has been is alleged to stem from S.N. Goenka’s 1969 advent of teaching the Vipassana techniques he learned in his native Burma (now Myanmar.) The tale of a Russian nobleman turning into a Buddhist sometime around the middle of the nineteenth century in a Dharma-denuded subcontinent sounds a wee bit fanciful.

Still, it is worth bearing in mind that Miguel Serrano was instructed in Tantric lore and practice during his decade-long stay in India during the 1950’s.(5) Additionally, Ungern-Sternberg would not have won the Kultuku’s favorable attention during the 1911 Mongolian-Chinese conflict without having some grounding in Buddhism. Centuries before the baron’s time, countless cashiered European military officers had reinvented themselves as soldiers of fortune across the steppes of Transbaikal, yet something made Ungern-Sternberg stand out. Given the exceptionality of Ungern-Sternburg’s personal fortunes, it is perhaps politic to accept the Polish man’s story about the Ungerns being a Buddhist family during the turn-of-the 20th century in Estonia.

Squaring the Baron’s stridently martial vocation with the pacifist roots of Buddhism presents yet another conundrum. In this case, it is worth remembering that that the contemporary Western conception of Buddhism represents a relatively recent caricature. At its root, the Dharma is not built upon soccer-moms and left-wing social-activists channeling boundless solicitude for the chronically dysfunctional while seated in full-lotus positions.

Rather, as Evola forcefully argues in his book called “The Doctrine of Awakening,” early Buddhism was an aristocratic warrior creed that was true to its Indo-Aryan roots. In its original from, rhe Dharma was open, but it was only open to those who were capable of withstanding this teaching’s demanding ascetic practices. In particular, the much-ballyhooed early Buddhist focus on compassion was cultivated as a DISCIPLINE, and not construed as the begin-and-end-all that it has become among the West’s “practitioners” of Buddhism. Within the auspices of the original Dharma, one exercises compassion to overcome ego, but not because compassion has its own intrinsic merit.

The Buddhism embraced by Ungern-Sternberg was of the Vajrayana or Tantric variety. In its native India, Vajrayana is heavily colored with the Indo-Aryan Hindu mindset where literally anything and everything manifests itself as an aspect of the Divine/the Dharma, including war and death. Further north in Tibet, the creed of Buddhism assimilates a good deal of Tibet’s indigenous Bön religion. In Mongolia, local shamanic practices derived from Tengrism hold sway over Buddhist practices. In both Mongolia and Tibet, the local permutations of Buddhism emphasize dealing with the world in all its harsh totality, rather than making attempts to “reform” all of the world into a mushy and gutless cosmic “safe space.”

One common element of Tantric Buddhism across all of its venues is an insistence on the viability of the “wet path.” According to tantric practitioners, sex, alcohol, and even violence can all be cultivated as spiritual disciplines, yet use of these tools within a spiritual context are hemmed in by a great list of stern caveats!

Image courtesy of baltimoresun.com

The final goal of Tantric Buddhism is to attain the highest measure of divinity possible for a given practitioner. Here, it is well to remember the words of Rudolph Otto who noted that our notions of divinity have essentially decayed into “ethics tinted with sentimentality.” In the older Aryan tradition, divinity, whether displayed by a god or a man, was conceived of as a sort of virile self-sufficiency characterized by a sang-froid to all circumstances and an insight into the karmic weight of all events. It is within this Tantric conception of Buddhism that Ungern-Sternberg sought to become a living incarnation.

Within the aegis of Tantric philosophy, the lines between the divine and humanity are not a fixed. As already noted, the Baron was seen as an avatar of various wrathful Buddhist deities by both the Mongols and Tibet’s Dalai Lama. The apotheosis of heroes is a frequent trope in Hindu epics, as it is in many strains of early European mythology. Indeed, Parzifal with his heaven-storming rage and subsequent elevation to the Grail’s King represents a late example of this spirit…as well as a template for Ungern-Sternberg’s career, though Von Eschenbach’s hero was rather more successful.

Image of a Parzival book cover furnished courtesy of abehbooks.com

Continuing along this line of thinking, the structure of the Parzifal legend offers a skeleton and framework for the Baron’s religious and political enterprises. In Hindu and early European mythology, a mortal hero attains apotheosis acting in a will-directed rage that permits the hero to overcome obstacles. Ungern-Sternberg was well versed in the books of St. Yves d’ Alveydre which developed Uralt teachings from a hidden kingdom called Agathara. The hidden kingdom of Agatha is said to exist somewhere in Central Asia within a trans-temporal realm that is ruled by a divine king named the Cakravartin. At least part of the Baron’s ill-starred attempt at an exodus to Tibet was driven by his fervent wish to contact the powers of Agathara.

Here we reach the crux of the matter: few people living today are able to appreciate the notion that violent conduct can be a spiritual discipline. (6) Present-day Western “ethics” represent a secularized rendition of the Nazarene’s dictum of “Resist not evil.” In the not so distant past, chivalry constituted the effort to fuse an Aryan warrior ethos with culturally-mandated Christian teachings. This effort to compromise Christianity with the trappings of common and universal warrior cultures worked for a few centuries, but this compromise came at a price. Within this early Christian system of epistemology, a warrior could still enjoy his martial achievements; however, such enjoyments always came at the cost of a bad conscience. Christianity’s “just war” theory postulates that combat of any type should be viewed as nothing more than a regrettable necessity, and combat should never be viewed as the telos of a warrior.

In the case of Christianity, fighters with burdened consciences are bad at what they do. Within our modern system, numbers compensate for faltering valor and technology serves as an ersatz counterpunch against eroded courage. In the end (or at least a great deal nearer it), the ethical foundation of Christianity renders fighting under any circumstances legally, morally, and mentally impossible. Witness today’s anarcho-tyranny in much of the West: an armed robber will often go free without posting bail and he will be charged with nothing beyond a misdemeanor. Likewise, a shopkeeper who draws and then uses an unregistered firearm to protect his business and his person against a robber will be charged with a felony and levied with an onerous bail.

Image of “This is Fine” meme furnished courtesy of ops.org

In the eyes of a Christianized legal system, virile initiative of the competent is construed as lèse majesté. Again, across the modern West news stories abound of Christian murder victims whose families forgive their child’s killer before their offspring’s corpse is even cold, such people then proceed to petition the courts for leniency on the “disproportionately impacted” delinquent who murdered their child. The overriding concern of contemporary Christianity is that violence must be avoided regardless of the cost. On this subject, a Confucian scholar’s exchange with a Jesuit missionary named Matteo Ricci that took place during the Ming Dynasty comes to mind, in this discussion the Confucian scholar remarked, “Love my enemies? Then what next? Hate my friends, my family, myself?”

Image furnished courtesy of 4archive.org

It is only against the backdrop of degenerate Christian ethics that we might recoil from the ethics of Ungern-Sternberg with such an extreme reaction. Bolshevik teachings stem from the same root as Christianity, and both Bolshevism and Christianity stem from the jabberings of old Jewish prophets. Likewise, Christianity and Bolshevism are both preoccupied with placing marginalized people into positions of power and prestige. Ungern-Sternberg’s reactions to many matters were undeniably rather extreme, yes, but were such actions excessive? This is harder to affirm. A victory against the forces arrayed against us today will be hollow unless the victors represent a new breed of men who are divine in the senses adumbrated above.

To speak of “victory” in 2023 may strike listeners as ironic because there is little to cheer and so much to lament and deplore. Presently, lady irony sings her siren song and her insouciant poses lend themselves to the gelding of what are rightly earnest matters, lady irony also sings as total defeat presents itself as the most likely outcome.

Part V.

The possibility that ours will turn out to be a losing cause is a truth that needs to be faced. The latter-day Gnostic Nimrod de Rosario hinted at a multiplicity of worlds where only one world sees our cause win. Cribbing from the South American sage named Miguel Serrano, we note that Serrano speculates that after our present Age of Iron sees its final curtain fall, the world will enter an Age of Lead.

On the face of what is arrayed against us, the best that can be said is that Kali Yugas have come and gone a great many times before. Quite likely, a Kali Age is something like a boot camp in the sense that every man who gets though these trying times is convinced that his experience was the most demanding and the bleakest time of his life.

Not surprisingly, present-day efforts to paint the baron as a broken man during his final days abound, yet true evidence proving that Ungern-Sternberg died a broken man is lacking. The Atlantic Magazine’s unsympathetic portrayal of the baron quotes his last words as such, “Ich bin immer ungern von Sternberg” and offers us a putative translation, “I have always hated myself!” Such words inevitably reduce Ungern-Sternberg to an exhibit of psycho-pathology .

Even if we accept this unattributed quotation sourced from the Jewish Atlantic magazine as genuine, then possibility still lingers that “Ungern-Sternberg” simply meant “reluctant” in this quote. In this case the baron might have been referencing reluctance in the sense that he was reluctant to embrace his own destiny, especially when his destiny included death at the ripe old age of thirty while carrying a basket filled to the top with unfulfilled ambitions. Like the Baron Ungern-Sternberg, Achilles, Hamlet, and Jesus, all had to steel themselves against their looming destinies. One might even take the Baron’s final words as gallows humor by implying that he made a pun on his name by implying, “I have always been reluctant to live up to myself, but behold, I do the thing anyway.” — even in the face of a firing squad!

In the baron’s case, some degree of reluctance to embrace his incredible destiny could not have been avoided because Ungern-Sternberg was one of the individuals that Savitri Devi styled “men against time.” One side to the Baron was that of an aristocratic Russian officer of the fin de siècle, and another side of the baron was summarized in the writings of Major Aleksandrowicz, “When one saw Ungern one felt himself carried back to the Middle Ages – the man’s boundless thirst for war and his passion for the supernatural.”

The last word on Ungern-Sternberg, which presents a challenge for us today comes from his remark already cited above. Informed that Kolchak was dead, Wrangel had fled, and Semenov fallen had away, the Baron declared, “This is no disaster but rather an honor.”

Dugin concludes his treatment of Ungern-Sternberg by suggesting how defeat here in this realm of effects is not necessarily a defeat in the world of spirit. Let us remember that Ungern faced his final moments in front of a Bolshevik firing squad while exuding a calm confidence that his story ddid not end on that day.

NOTES:

- Even with the sorry and sanguinary history of the Soviet Union, Western historiographers remain locked in the narrative, “Czarists bad/Communists good, though perhaps a bit overzealous.”

- Interestingly, as Ungern’s reputation spread, the unit even attracted a detachment of Japanese volunteers with Shingon (Vajrayana) convictions.

- Woodrow Wilson privately remarked in 1917 that he had never become President had he known he would be taking orders from Jacob Schiff. Schiff, recall, was the Wall Street magnate who heavily subsidized the Russian Revolution through his Semite co-religionists implementing and leading that revolution.

- “The Buddhist God of War Who Foreshadowed ISIS,” 2 FEB ’16, theatlantic.com

- Tantra seems to have sprung up within both Hinduism and Buddhism circa 500 A.D. Serrano’s discussion dwells at length upon Siva, yet he freely interlards Buddhist references as well. His actual gurus seem to have all been Hindu, albeit well-versed in Buddhist scripture and lore.

- Evola’s “The Metaphysics of War” is, of course, the place to start cultivating that appreciation. One might consider, as an interesting parallel with Vajrayana’s sometimes martial Buddhism, the development of the Christian Identity movement in the West. Here “gentle Jesus meek and mild” is recast as a virile hero after the classical mold. While an outsider might find this forced and point to the slim Biblical basis for the reworking, the fact remains that a number of individuals draw strength from the seemingly unlikely pairing of the Christ and the Führer.